In this report, Arinze Chijioke looks at how delays in the evacuation of waste in Enugu State encourage indiscriminate waste disposal, its health implications, and how the practice impacts the environment.

As Benjamin Eze walked towards a waste dumping site in the Asata Area in Enugu State, South-eastern Nigeria one afternoon in early January 2022, he discovered that the five waste dumpsters were filled and overflowing and that residents were beginning to drop their waste on the ground.

Quickly, he threw the two nylon bags he had used to pack his waste close to the dumpsters and left, covering his mouth and his nose. The stench emanating from the dumpsite was unbearable.

“I had intended to use the bin but when I got here and discovered that they were all filled up, I decided to drop it like every other person, “he said. “I could not have taken it back home”.

It had been four days since the dumpsters were filled up with heaps of littering wastes around. But the workers who would always come with trucks to clear them had not come. The situation makes work difficult for Okafor Chiemelie who offers graphics design services close to the dumpsite. He says it’s difficult to work inside his office whenever the wastes are left unpacked.

“Whenever it rains, it is hard to pass through the area, “he said. “Most of the time, rain pushes the wastes into water channels, making it hard for water to freely flow to its destination”.

Overflowing dumpsters at Ebelane

Heaps of waste at Enugu’s main market

Like Chiemelie, residents living close to the dumpsite and business owners, particularly food sellers who shared their experience with this reporter said they have had to endure days and weeks of unbearable stench. They say it affects their business because those coming to eat would always complain about the smell and find alternatives.

But the situation is not peculiar to the Asata area of the state. Today, It is common to walk around Enugu State and find wastes generated from households, eateries and offices strewn everywhere, on both sides of some roads, some of them making their way into water channels.

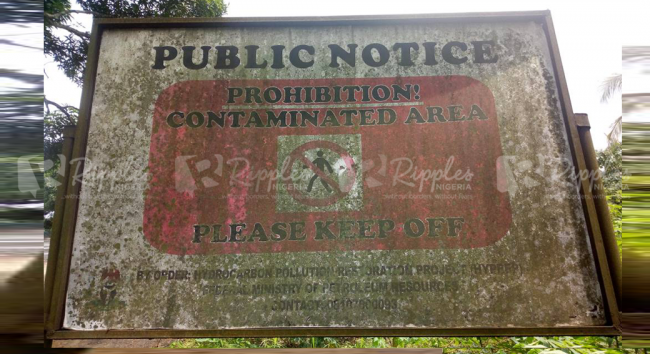

From streets to motor parks and from markets to schools and hospitals, the indiscriminate dumping of refuse- occasioned by delays in evacuation has increased to a devastating and uncontrollable rate, contaminating the environment and exposing residents to serious diseases.

Heaps of waste at Obeagu

An overflowing dumpster at Okpara Avenue

Health and environmental concerns

Improper disposal of waste particularly plastic waste, typified by overflowing dumpsters, and mountains of open refuse dumps, remains a major environmental and public health concern prevalent in most developing countries.

Apart from causing damage to the eco-systems and accelerating the destruction of the environment, the situation exposes humans to widespread diseases such as cholera, diarrhoea and typhoid fever.

Waste inside the University of Nigeria, Nsukka

Waste inside Parklane, Enugu

Gboyega Olorunfemi, Principal Consultant, EnviromaxGlobal Resources Limited, Ibadan, said that improper waste disposal also causes malnutrition and stunting in children as well as respiratory illness, risk and exposure to contaminated water and food.

“Waste dumped indiscriminately clogs the drainage channels and leads to flooding during the wet season and could also lead to fire outbreak,” he said.

Apart from institutional weaknesses on the part of the government, as is the case in Enugu, uncontrolled population growth and lack of awareness increase the rate of Improper waste disposal.

Marine species under threat

About 300 million metric tons of plastic waste are produced each year globally. But out of the more than 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic estimated to have been produced since the early 1950s, about 60% has ended up in landfills, dumps or the natural environment. Only 9% of all plastic waste ever produced has been recycled. About 12% has been incinerated, according to a report by Science Daily.

Much of the world’s plastic- an estimated 8 million metric tons every year- has ended up in the world’s ocean. Of major concern is the fact that these plastic items do not fully disappear.

Although they have a lifespan of mere minutes to hours, they often contain additives that make them stronger, more flexible and durable, persisting in the environment for at least 400 years, a national geographic report shows.

As they get smaller and smaller, they are swallowed by farm animals or fishes in the river who mistake them for food. Millions of these animals are killed by plastics every year, from birds to fish to other marine organisms.

The report shows that nearly 700 species, including endangered ones, are known to have been affected by plastics. It is feared that If the current trend of waste mismanagement continues, our oceans could contain more plastic than fish by 2050.

A more worrying concern

Apart from delays in waste evacuation in Enugu State, there is a more worrying concern about the open burning of wastes. It is common to walk across streets and find dumpsters burning, posing

According to Olorunfemi, the open burning of wastes releases substances into the air that are toxic, many that are carcinogenic and are also called short-lived Climate pollutants e.g.: black carbon, dioxins, Mercury, Furans and PCBs (Polychlorinated Biphenyls).

He said that these substances lead to cancer, asthma, heart diseases, skin and eye diseases, causing damage to nervous and reproductive systems, although it is difficult to determine the true level of impact of open burning of waste on public health because not much data is available in Africa.

“The black carbon contributes to climate change by warming the earth through direct and indirect interactions with clouds and rainfall patterns “he added.

Overflowing dumpsters at Asata

One of the rickety trucks used to evacuate waste

When contacted, the former Com

“It is usually done at night and we are not happy about it,” he said. “But we cannot police all dustbins in the state and even when people see the bins burning, they don’t care to put it out”.

Edeoga who resigned following his interest in contesting for the governorship position said that the government had tried severally to end the burning, yet it continues. But while the former commissioner claims the government is not aware of those setting the wastebins on fire, many residents claim they have seen those in charge of evacuating the wastes burning them.

Where the Enugu problem lies

The reason for the recent wave of delays in waste evacuation is said to be linked to the decision by the state governor, Ifeanyi Ugwuanyi to create a committee on waste evacuation out of an already existing waste management body, Enugu State Waste Management Authority (ESWAMA) according to a source who would not want his name mentioned.

While the government stopped ESWAMA from carrying out its primary responsibility of evacuating wastes, it handed it over to the committee which went ahead to hire trucks-which break down regularly- and workers who take weeks to clear wastes.

He explained that while ESWAMA- which is under the ministry of environment collects levies from households, it asks the committee- which is now directly under the governor’s office- to evacuate wastes, which they often fail to do.

One of the rickety trucks used to evacuate waste does not have a fuel tank

“After the levies are collected from households and given to the government, the government, in turn, hands the money to the committee and they are still not working,” the source said. “And there is no form of collaboration between ESWAMA and the new committee”.

He told Econai+ that the State House of Assembly had invited the two bodies after it received several complaints of delays in waste evacuation. But the chairman of the committee refused to say what the problem was and insisted that he was only answerable to the governor.

A former senior staff of ESWAMA, who prefers not to be mentioned confirmed that the delay in waste evacuation began after the state government decided to strip the agency of its responsibility for waste disposal and handed it over to a committee.

“I cannot exactly say why the governor asked us to stop doing our work,” the former staff said. “ He is aware of what is happening to waste management in the state and what ESWAMA does not is to basically supervise and generate revenue for the state”.

Now, households who are paying levies at the GRA, New Haven and Independence Layout areas of the state are complaining that even after paying N10,000 to 15,000, there is a delay in waste evacuation.

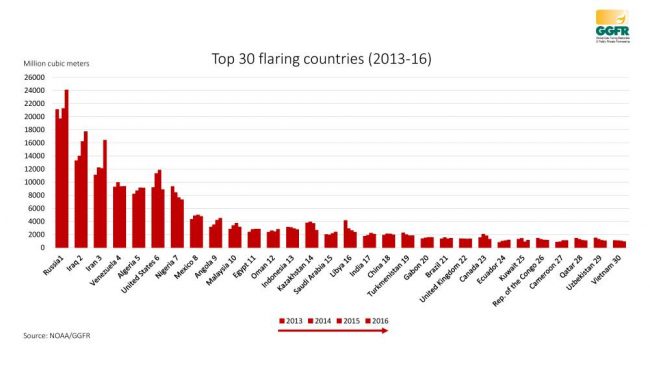

Impact on climate change

Several reports have shown that unmanaged dumpsites are major sources of Green House Gas emissions (GHGs) and emission of water/atmospheric pollutants as well as odours in developing countries.

About 80% of solid waste in African countries, for instance, is dumped indiscriminately in open spaces, streets, stormwater drains, rivers, and streams thereby, contributing to an estimated 29% of the global GHG emissions which is expected to increase to 64% by 2030.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had warned that if actions are not taken to prevent the continual increase of GHG emissions, the Earth’s temperature will increase by 6.4 °C in the 21st century. Without improvements in the sector, solid waste-related emissions will most likely increase to 2.6 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent by 2050, according to a world bank report.

What happened to Enugu’s waste compactors?

When the administration of former governor Sullivan Chime came on board in 2007, it introduced a modern scientific approach to refuse collection, disposal and solid waste management by procuring more than 15 waste disposal compactors and over one hundred dumpsters which were deployed in all parts of the state capital and Nsukka Urban.

In collaboration with other departments and agencies, the Environment Mini

The Ministry had been established in Enugu State in 2004 to improve the beauty and aesthetics of the physical environment and adequate protection of the ecosystem and effectively manage solid wastes in the state.

A building affected by open burning of waste

The Enugu State Waste Management Authority (ESWAMA) an establishment under the ministry also introduced monthly sanitation exercises and street by a street collection of refuse on daily basis.

In 2011, the administration took a delivery of 285 refuse bin holding pads, built 283 conventional refuse bin slabs and fire motorized bin slabs on major urban roads in the state capital and Nsukka.

The governor also approved the purchase of earthmoving equipment for ESWAMA, including three tippers, two bulldozers and pail loaders each, reportedly worth three hundred and twenty-two million naira (N322 million).

According to Chuks Ugwoke, who was the State Commissioner for Information at the time, the decision to purchase the equipment was in keeping with the resolve of the Chime administration to ensure and maintain a very clean and healthy environment in the state.

Sadly, seven years after the Chime administration left power, the current administration has failed to effectively manage waste in the state, depending on rickety trucks which take days to clear waste. The administration has also failed to maintain the waste disposal compactors which had been provided for waste management.

Burnt dumpsters at Independence Layout

Beyond Enugu, there is no commitment to tackle plastic waste in Nigeria

A 2018 report by the World Economic Forum estimates that Nigeria for instance, generates some 32 million tonnes of waste per year, out of which a staggering 2.5 million tonnes are plastic. While the country’s annual plastics production is projected to grow to 523,000 tonnes by 2022, it is estimated that the country discharges 200,000 metric tonnes of plastic waste into the Atlantic Ocean each year.

But In 2018, the minister of State for Environment, Alhaji Ibrahim Jibril, said the federal government was working on a national policy on plastic waste management to regulate the use and disposal of plastic waste in the country.

At an event to mark the 2018 World Environment Day, Jibril said the ministry had collaborated with stakeholders and developed a national strategy for the phase-out of non-bio gradable plastics as well as developed a national plastic waste recycling programme, to establish plastic waste recycling plants across the country.

The facilities were expected to complement the efforts of various state governments at facilitating a clean environment and preventing environmental pollution from solid waste disposal in Nigeria. Jibril announced that a total of eight plants had already been completed and handed over to the states while 18 others were at various stages of completion.

However, investigations have shown how some of these plants reported having been completed in Osun, Ekiti, Lagos and Kaduna or ongoing were wasting away despite the government’s huge investment in the project.

With inefficient disposal, recycling, and waste management system, an overall 70% of plastic and non-plastic waste produced in Nigeria end up in landfills, sewers, beaches and water bodies.

Nigeria’s plastic bag prohibition bill

The House of Representatives in 2019, passed a bill banning plastic bags in the country. It was intended to address the harmful effects of those plastic bags on the oceans, rivers, lakes, forests, environment, wildlife as well as human beings and to relieve pressure on landfills and waste management.

The Federal Executive Council (FEC) had also approved the Solid Waste Management Policy for Nigeria to provide a framework for a comprehensive integrated solid waste management which the federal, state and local governments, MDAs, institutions and NGOs will be part of.

The bill provided for: “An act to prohibit the use, manufacture and importation of all plastic bags used for commercial and household packaging in order to address harmful impacts to oceans, rivers, lakes, forests, environment as well as human beings and also to relieve pressure on landfills and waste management and for other related matters.”

Littering waste at New Haven

It described as an offence the failure to provide customers with paper bags, manufacturing plastic bags for the purpose of selling, and importing plastic bags “whether as a carryout bag or for sale”.

Any person found guilty of the offences shall be liable upon conviction to a fine not exceeding N500,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or to both such fine and imprisonment, according to the bill which also prescribes a fine of N5 million to companies guilty of the offences.

But two years down the line, the Nigerian Senate is yet to consider and transmit the bill to President Muhammadu Buhari for assent. If drastic measures are not taken, It is estimated that Nigeria would be the nation producing the largest amount of mismanaged plastic waste in Africa by 2025.

Another waste dumpsite in Enugu

Need for Investment in the waste recycling value chain

A 2018 World Bank report projects that rapid urbanization, population growth and economic development will push global waste to increase by 70% over the next 30 years to a staggering 3.40 billion tonnes of waste generated annually.

The same report showed that successful interventions are needed to improve waste management which will help cities become more resilient to the extreme climate occurrences that cause flooding, damage infrastructure and displace communities and their livelihoods.

Responding to this, Olorunfemi said that state governments must realize that waste recycling is one of the numerous value chains in waste management and it is one of the ways materials can be recovered, reused and repurposed.

“Waste recycling enterprises will bring about improvement in air and reduction in carbon emission”, he said. “When you recycle, there is a reduction in the volumes of waste that gets burnt or goes to the dumpsite, reduced stress on the exploitation of natural resources. It creates the prospect for wildlife and ecosystem protection and it provides an opportunity for generating employment”.

He said that the Federal government must review existing policies to accommodate global best practices with the integration of native intelligence and innovation, and provide tax incentives to entrepreneurs who are willing to commence or augment their enterprise in the sector to scale.

“This may not create a waste-free environment immediately, but it will build a foundation to which its success will depend, he said, adding that consistent and sustained advocacy and engagement with the government will make them realize the need to fund the sector that is currently suffering for lack of creativity and capacity on the part of the regulators.