By Frederick Clayton and Sonja Smith

Photography by Margaret Courtney-Clarke

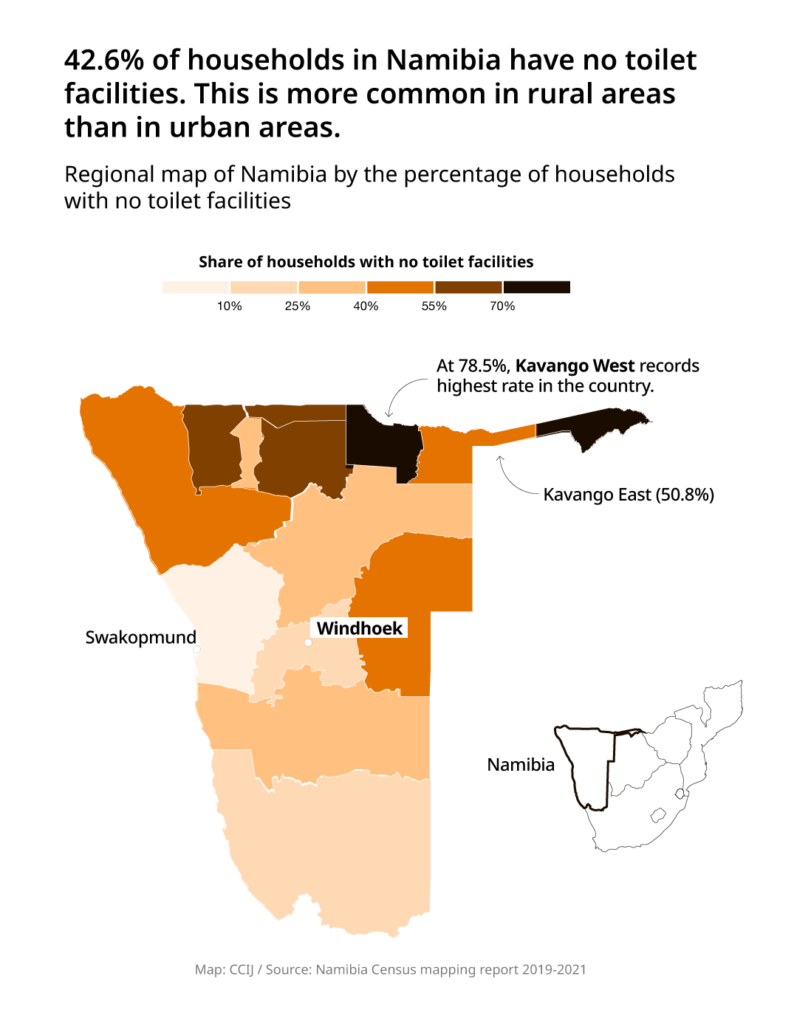

Ever since independence, Namibians have sought education, employment and better lives in Windhoek, the country’s political and industrial epicentre. It’s harder to make a living in rural Namibia – southern Africa’s driest savannah – where there’s little to no infrastructure, investment or industry. With so few opportunities to work and study, thousands leave for the city every year, and the capital’s population has tripled since independence.

2022 – In Max-Mutongolume, an extension of the Havana informal settlement outside of Windhoek, toilets built by Development Workshop Namibia in 2019 for the Smart Kindergarten preschool are kept locked at all times for fear of vandalism. To use the toilets, which are painted with instructional graphics on how to use them properly, children are accompanied by a volunteer supervisor.

This influx of migration has stretched the city’s limits and worsened sanitation. Informal settlements, like Havana, have expanded uncontrollably as people arrive faster than Windhoek can provide services. These newcomers build shacks in tiny pockets of space without any regulation, arrangement or design.

“There’s no structure, no planning; you cannot put in water pipes,” said Sebastian Husselmann, Windhoek’s chief engineer for bulk and wastewater. “How do you put a sewage network in an unplanned area?”

Conditions here are perfect for the spread of disease as overcrowding leads to the cross-contamination of faeces, water and food. “Some of them are 19, 20, 35 in one house. One toilet for 35 people – it’s not healthy or hygienic,” says Councilor Rodman Katjaimo.

This is where Hepatitis E hit hardest, accounting for 62% of confirmed and suspected cases during Namibia’s recent outbreak, which started in 2017.

2019 – An oryx suffered a common fate for many wild animals in the arid Namib desert of western Namibia. The poorly maintained fences surrounding the national park separate wildlife from the few sources of water that exist on neighboring private land. In their search, the animals will try to jump the fence, only to end up trapped and mauled to death by jackals, vultures or hyenas

In the run-up to the 2019 elections, President Hage Geingob declared living conditions in informal settlements a “humanitarian crisis” and promised to rid cities of shacks before 2024. But this hasn’t happened. In Windhoek, they are now growing at a rate of 10% each year, according to Sade Gawanas, the city’s former mayor and member of the Landless People’s Movement Party.

Namibia’s urban and rural development minister, Erastus Uutoni, declined to comment on the government’s failure to slow the growth of informal settlements, but, in February 2023, he said Namibia faced serious sanitation problems if urbanization was left unchecked. He called on local authorities to direct budgeting toward sanitation infrastructure and upgrading the informal settlements.

Ten years ago, Letisia Nghiondjwa, 44, moved to Havana with her husband from Okanguati village in northern Namibia “for a better life.” She makes a living selling fat cakes — fried dough coated in sugar — and oshikundu, a traditional Namibian brew. But she and her husband are two of many who have been squeezed into dangerously squalid conditions.

“We live by the dumpsite, and when it rains you cannot sleep [because of] the smell,” she says. “It’s been 10 years now, and nothing much has been done by the government to make our lives easier… We sleep in sewage.”

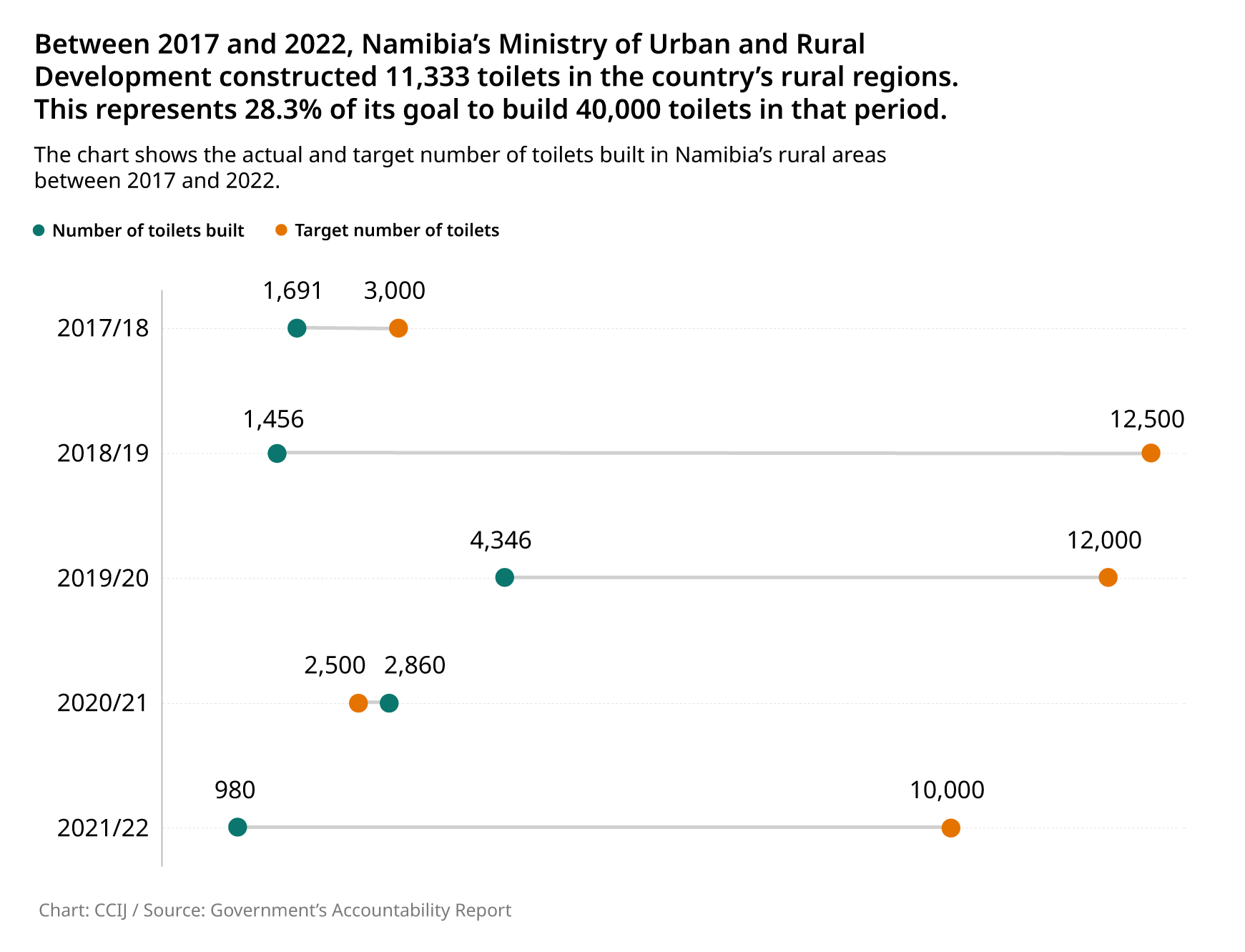

Across the political spectrum, ministers, politicians and councillors have called for greater investment in rural areas, and yet Namibia’s rural development and coordination budget dropped 33% between 2019 and 2022, according to CCIJ’s analysis.

2022 – Martin Bonafatius, 32, and his neighbors work to extend a communal water point to the next neighborhood in Kavango East in northern Namibia. The government installed one tap for a large community, and so residents have chipped in to buy pipes and dig trenches to extend the line. Two 100-meter pipes cost N $5800 (or about $400), as well as a free dayÕs labor from six men. The first tap was installed in the 1990s. The residents have built seven more since 2020. ÒWe donÕt want to die waiting for [the] government,Ó he says.

The government must act soon if it wants to address this growing issue. Urbanization is creating conditions that lead to more death and disease as settlements like Havana expand, and climate change is exacerbating the problem as persistent drought conditions for the past seven years have left many in rural Namibia who depend on crops and livestock jobless.

Simon Dirkse, head of climate at Windhoek’s Meteorological Institute, was pessimistic in his assessment of Namibia’s future and the impact of more extreme weather events. “Yes, climate change is forcing migration,” he said, adding “our poverty levels and these extreme events don’t go together.”

But people need to work. Selma Mpasi, 21, who sits in the shade selling oranges by the side of the road with her two-year-old daughter sleeping on her lap, said business is slow, with fewer tourists passing these days. “Our lands are so dry,” she says. “I want to go to Windhoek.”

2022 – Two typical government toilets in a state of disrepair in Havana, an informal settlement on the outskirts of Namibia’s capital.

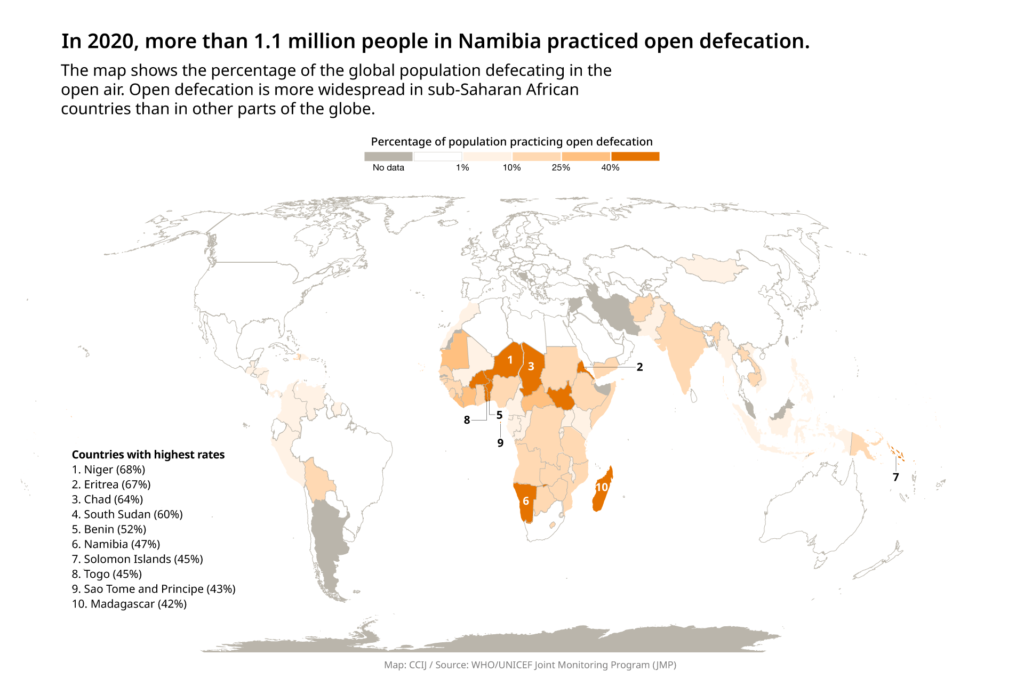

Namibia is one of many countries in Africa struggling with the harshest impacts of climate change, but here the issue is amplifying the lack of adequate sanitation in and around cities.

Attempts to fill the sanitation gaps

Ndahambelela Indongo, 39, lives in Max-Mutongolume, a community inside Havana informal settlement. She used to walk for an hour into the hills to find a safe space to defecate, but after learning about the negative health effects, she built her own toilet and tippy tap – a hygienic hand-washing mechanism that uses running water.

Indongo got her information from a sanitation center run by Development Workshop Namibia (DW), an NGO that has helped communities across the country become open defecation free (ODF) – status granted when a community shows an ongoing adoption of good hygiene practice and all its members have access to sanitation facilities, with at least 80% of residents using them.

DW does this by using Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), a collaborative, bottom-up approach aimed at achieving and sustaining ODF free status by focusing on “igniting a change in sanitation behaviour through community participation rather than constructing toilets.” Facilitators trained on CLTS help community members understand the consequences of open defecation, which they hope will lead to mobilization, a demand for sanitation and the community deciding for themselves what action they will take.

Since its inception, DW says it has built 66 sanitation centers in public spaces that each include a demonstration toilet to incentivize residents to build their own. To date, it claims it has trained 323 local brick-layers in toilet construction, who can then offer their services to assist residents. (CCIJ has not been able to independently verify those figures.)

In the absence of government-backed sanitation services and information campaigns, schemes like these have helped transform informal settlements and rural communities by creating a demand for sanitation and motivating residents to invest in solutions. But only 13 areas in Namibia are currently ODF.

2022 – Roughly 90 kilometers outside of Rundu, Namibia, Mr. Hangura, 84, was en route from his far-off resettled farm to collect water for his family but got stranded with a punctured tire. While his oxen graze in the bushes, he waits for a grandson to return with a repaired inner tube, which he says could take two days.

Organizations like DW and UNICEF cannot facilitate this kind of change nationwide, and Shuuya is realistic about what Namibia can accomplish without government support. “We are not going to be able to achieve the SDG6 goal unless something drastic happens,” he said. “We need a national campaign with proper government leadership to promote the importance of sanitation. That would really make a change.”

Reasons for hope

Since the turn of the millennium, the number of people using basic sanitation services in Botswana has increased by 28.1%, and the country was among just a handful of sub-Saharan nations to achieve the UN’s Millennium Development Goals of halving the number of people without access to basic sanitation by 2015, doing so five years ahead of schedule.

Botswana continues to improve sanitation by actively advocating and improving legislation while promoting hygiene. In 2017, the Ministry of Land Management, Water and Sanitation Services laid out its responsibilities of “coordinating and monitoring sanitation services,” managing “on-site sanitation” and improving WASH services alongside the Ministry of Health.

Botswana has also invested in both wet and dry sanitation. And, since 2001, the government has allocated almost a fifth of its budget to health care every year.

The nation now faces its own challenges in reaching zero open defecation by 2030, as diarrheal diseases remain a prominent concern, and there is still a stark gap between urban and rural sanitation levels. But Botswana’s government understands that prioritizing sanitation and public health underpins economic growth and better living conditions, which is reflected in deliberate strategy and policy.

By contrast, progress in Namibia has faltered. However, there is still a chance that the country will embrace more aggressive investment and focus on improving sanitation by raising awareness and working with communities.

SWAPO’s 2021 Harambee Prosperity Plan II allocated N$120 million ($8 million) to officially launch CLTS in Namibia and “increase WASH awareness through the community construction of latrines.” The government has also trained staff from four ministries on CLTS, while the latest draft of Namibia’s 2022-2027 National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy combines “awareness development” and “changing social norms” with providing infrastructure.

Later in 2021, the government also launched the Namibia Water Sector Support Programme (NWSSP), one of the nation’s biggest ever infrastructure projects aimed at directly improving sanitation for 1 million Namibians, funded by a $121.7 million loan from the Africa Development Bank in 2019. Targets include reducing open defecation in rural areas to 55% by 2025 and ensuring access to improved sanitation services for all Namibians by 2030.

2019 – Though living in a country plagued by hardships, Selma Jacobs performs a traditional rain dance across the barren Omongwa (ÒSaltÓ) Pan in eastern Namibia. Of prime importance to the Kalahari bushmen/San groups are ritual dances that serve to heal the group. Here Selma goes into a trance dance while women clap their hands and chant to her altered state of existence. Birth, death, gender, rain and weather are all believed to have supernatural significance.

When the project was launched in August 2021 by Calle Schlettwein, Namibia’s Minister for Agriculture, Water and Land Reform, he urged service providers, contractors and consultants not to cut corners and appealed for “accountability, transparency and a corruption-free atmosphere to prevail.”

This sounds good on paper, but after more than a year, the scheme’s major projects are still in the design and procurement phase. Schlettwein’s office admitted that the NWSSP had had “a slow start” and that “much more funding” would be required to meet SDG6.

Lukas Shilongo, 21, who lives in Havana, is already skeptical. “They make campaigns, lie to us, then they forget,” he said. “They promise us water, electricity, toilets. [They don’t] come.”

Gawanas, the former Windhoek mayor, agreed that leaders had used sanitation as a campaign tactic during elections and later broke their promises. “I don’t think [politicians] want to solve the problem,” she said. “They want to keep people begging for more because it is their tool to stay in power.”

Geingob was reelected as president for a second term in 2019. However, that election saw SWAPO’s vote percentage drop significantly from 87% in 2014 to 56% — its biggest loss of support in the nation’s history, as drought, recession and a massive corruption scandal weighed on voters.

2022 – By this time of year, in the rural Kavango East region of northern Namibia, residents would usually be plowing their farms. Now that the rain arrives two months later, their only business is to sell oranges on the roadside.

As Namibians return to the ballot box in 2024, they may be tired of begging for their human rights, too. As SWAPO’s electoral dominance fades, politicians of all parties and at every level could be forced to keep their promises on sanitation services, or risk being held accountable at the polls.

Alfons Kaundu, a Mbunza traditional authority chief in rural Namibia, thinks that’s a possibility. “People are suffering here,” he said. “The government is not respecting people’s rights. [But] maybe the next election is going to be different.”

Namibia’s rural development and coordination budget drop was calculated using Vote 17 found in Government Accountability Reports from 2019-2020 and 2021-2022.

This report was produced by the Centre for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ), a non-profit organisation that brings together investigative reporters, visual storytellers and data scientists to investigate key global issues affecting communities. This report was supported by the Pulitzer Centre.