By Frederick Clayton and Sonja Smith

Photography by Margaret Courtney-Clarke

In 2012, a UN special rapporteur said Namibia’s sanitation deficit was due to a “lack of a common vision” and an “absence of effective coordination among the different ministries.” In 2023, these are still the biggest obstacles to improving sanitation.

Xhuka Shorty and his family are San, an indigenous group of people in southern Africa. Eight years ago, he and 16 members of his family were evicted from the farmland where they had lived and worked as labourers for generations.

Left to survive off Shorty’s monthly pension of N$1300 ($87), they migrated to Katumba village in northwest Namibia, where they lived under the shade of a tree. One day in 2019, the government installed a toilet next to Shorty’s tree. “What am I supposed to do with this?”, he asked.

Shorty was given a dry toilet — a type of toilet that uses no water or chemicals to move waste along. Instead, excrement drops into a tank or bag that must be emptied and cleaned. The lifetime costs of dry toilets are lower than that of flush toilets as they save on water, and some even produce fertilizer from the dried waste. In southern Africa’s driest country, where sewage connections reach just 35% of citizens, they are vital to providing sanitation.

But they do require more work. There’s no water seal to protect from the smell, so things can get ugly quickly without daily cleaning and good ventilation. Every so often the tank must be emptied. And if the toilet is a pit latrine, then one must dig another hole and move the pot before next use. There are also things you can’t always put down the hole – such as water – and, like all toilets, sometimes they need fixing.

None of this is obvious, especially if you’ve never used one.

2022 – A self-built shower, locked with wiring, by the side of the road in Havana informal settlement on the outskirts of Windhoek, Namibia. Photo: Margaret Courtney-Clarke

In 2012, after visiting Namibia, the UN’s special rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, Catarina de Albuquerque, outlined that public participation “in the design, implementation and monitoring” of toilet initiatives would be indispensable in providing the country with sanitation. She also warned that the benefits of investing in sanitation would be lost if the government failed to give equal attention to “hygiene promotion and awareness raising on the benefits of safe sanitation.”

Simply put, building toilets would not guarantee their use. People must want to use them, but to create that incentive many Namibians, who had lacked adequate sanitation for decades, would need to be educated on the benefits and instructed on proper cleaning, maintenance and hygiene.

The government acknowledges this. In fact, the government’s 2008 Water Supply and Sanitation Policy outlined that improving sanitation would be achieved by “community involvement and participation.” And yet it appears it has not followed its own guidance.

In 2012, the government constructed 10,000 dry Ecosan toilets across five northern regions at a cost of N$181.5 million ($22.4 million), but many are no longer usable because residents say they were not provided with instruction, promotion, cleaning or maintenance guidance upon installation.

Paulus Mutikisha, the headman for Ekolanaambo, a village in northern Namibia’s Oshana region and one of the beneficiaries in 2012, told the Namibian Sun in 2019, “We have never used [the toilets] because we were never trained on how to use them,” adding that some facilities were not installed properly. ”Money has been wasted, and the structures are… falling apart,” he said.

2022 – From their home in Katondo village in Kavango West in northern Namibia, Elizabeth Katota and her family walk down to the infested Okavango River each evening– as do so many families. Photo: Margaret Courtney-Clarke

In 2014, many beneficiaries of a scheme that aimed to build 6,500 pit latrines across the country returned to the bush to defecate. Residents of the Coblenz and Okondjatu villages in central Namibia complained about the stench, bemoaning their inability to keep the toilets in good condition. “We only have a few of these dry pit toilets, and as much as they are helpful, we are challenged when it comes to their maintenance,” Unjee Usora told the Namibian. “At the end of the day, the toilet is filled with faeces.”

The latest draft of Namibia’s 2022-2027 National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy, reviewed by CCIJ, accepts that “[u]ser involvement in the choice of sanitation systems and their construction, operation and maintenance [was] limited… [leading] to sanitation facilities not being used, operated or maintained properly.”

Flush or dry, providing sanitation is not just an infrastructure project, and the government is aware of this too. It was the duty of the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform (MAWLR) to organize “the training of communities on operation and maintenance,” according to the government’s 2010-2015 National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy. The Ministry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS), meanwhile, was responsible for conducting “hygiene education in rural areas and informal settlements.” But this doesn’t appear to have happened.

In fact, according to the latest draft of Namibia’s 2022-2027 National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy, MAWLR and the Ministry of Urban and Rural Development (MURD) alone built 20,230 sanitation facilities between 2009 and 2019, yet “no community involvement and participation or sanitation hygiene promotion activities were incorporated.” During those 10 years, open defecation dropped by just 2.7% nationwide, while sanitation levels in urban areas actually declined.

CCIJ asked Dr Elijah Ngurare, MAWLR’s Deputy Executive Director for Water Affairs, why Namibia had failed to engage communities in training and operation or to run a national campaign promoting hygiene. He said, “Sanitation challenges have been acknowledged and the government has now decided to scale up the process… construction, maintenance and rehabilitation is going to be the norm. This includes both rural-urban and rural sanitation.”

But the government has made implementing such strategies as complicated as possible. Rather than centralizing responsibility for improving sanitation, seven ministries, regional councils and local authorities have each been tasked with its delivery: MAWLR, MoHSS, MURD, the Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture (MoEAC), the Ministry of Environment Forest and Tourism (MEFT) and the Ministry of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare (MGEPESW) each have funding for sanitation in their budgets.

Meanwhile, local authorities – partly funded by the central government – are responsible for providing sanitation in urban areas, including informal settlements, and the Ministry of Work and Transport (MWT) is responsible for developing new and managing existing wet sanitation systems.

This division of duties and funding makes it especially difficult to monitor and track investment in sanitation, as well as Namibia’s adherence to the 2015 Ngor declaration, in which the government promised to annually commit a minimum of 0.5% GDP to sanitation and hygiene from 2020 onward.

The latest version of Namibia’s 2022-2027 Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy acknowledges that the government and local authorities “do not have a clear budget line for sanitation… As a result, the sanitation budget is… difficult to track.”

Shuuya of UNICEF Namibia said this contributed to poor coordination of the sanitation sector, something the government admitted in its 5th National Development Plan. “The sector is… not playing together,” he explained, adding he was desperate to see the Namibian government develop a separate sanitation budget so that it could monitor funding moving forward.

The consequences of insufficient governance are evident in surveying the Namibian landscape. Damaged, disused and derelict government toilets can be found across the country. Often, they are filthy beyond use, blocked by a newspaper or filled with excrement, and a considerable number no longer function.

2019- Xhuka Shorty, aged 102, and his family settled under a tree in Katumba village, now a Herero settlement in the Otjozondjupa region of Namibia, in 2015

Cutting corners

At a time when sanitation is in desperate need of a dedicated, coordinated and potentially more costly approach, those in the private sector say the government has complicated their efforts to provide more sustainable options.

Eline van der Linden is the executive director of Omuramba Impact Investing, the sole distributor of a dry toilet called the Enviro Loo. Unlike the ventilated pit latrines preferred by the government, her toilets reduce odor by separating waste from urine and are built with a closed container that prevents groundwater pollution. Crucially, she also offers user and maintenance training upon installation — including refresher courses on cleaning and maintenance with locals who can then charge the community a fee for their services as cleaners or janitors.

But the technology and training come at a higher price tag, which is why van der Linden no longer bids on government tenders. Her cost simply exceeds government specifications.

“[The government] thinks cheap solutions will last,” said van der Linden, who has never seen training included as part of a tender. “When they do put dry toilets down, they do it without any additional effort… No toilet system will work without educating communities on daily cleaning.”

A proper approach is not as cheap and easy as simply building toilets, but it has proven effective. In 2010, German development agency Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) supported the Omaruru Basin Management Committee (OmBMC) in central Namibia by providing 140 residents inside an informal settlement with 21 dry Otji toilets, designed by Namibian NGO Clay House Project (CHP).

CHP staff built the toilets while training local labourers how to do so too, and nurtured a sense of ownership as beneficiaries made a small financial contribution and assisted in painting and digging. Each toilet was equipped with instructions and handwashing facilities, and CHP also conducted an awareness-raising campaign to promote the use of toilets which remained in use and well maintained more than 18 months later. The OmBMC said there was even demand for 100 more.

But more toilets required additional funding or subsidies from the Municipality of Omaruru via MAWLR. As well as their relatively high cost, the local authorities also considered them inferior to “high-class” flush toilets despite the extra maintenance, construction and operational costs of flush toilets. A 2012 CHP report on the Otji toilets concluded that “[w]ithout the support of decision-makers, it will not be possible to establish a dry sanitation system on a large scale.”

Van der Linden says she has encountered the same stubborn obsession with flush toilets, and markets her toilets as a sustainable “in the meantime solution” for people who will one day, ideally, have flush. Her Enviro Loos, like Otji toilets, are not the cheapest on the market, but she thinks that instead of investing larger amounts in the best dry toilets, the government would rather wait to score points with flush toilets. “They do not see any benefits in dry sanitation,” she added.

Shuuya says there’s some truth in this. Under the apartheid regime, which preceded Namibia’s independence, “flush toilets were the preserve of the colonizers, the white people,” he explains. “Blacks were provided with pit toilets and bucket toilets.”

Namibia’s Minister for Health and Social Services, Dr Kalumbi Shangula, declined to comment on the historical connection, but Shuuya argues that this helps explain why many Black Namibians still perceive even quality dry toilets as inferior.

“But then there are practicalities,” Shuuya notes. “You can only have a flush toilet when you have water.”

Windhoek rural constituency councillor and member of the opposition party the Popular Democratic Movement, Petrus Adams, has flush toilets in his town, Groot Aub, but residents don’t always have enough water to use them. “[But] open defecation,” he says, “what does it cost?”

In a country where almost a third of citizens worry about where their next meal will come from, many can scarcely afford the 16,000 litres of extra water it costs to flush a toilet per person each year.

“Wet sanitation risks making unaffordable water even more unaffordable,” added de Alberqueue, the UN’s special rapporteur who urged Namibia to promote dry toilets in her 2012 report, warning that if people continue to perceive dry toilets as inferior, they would never embrace them. But she advised that no one size fits all, and that “communities and households must have choices about which sanitation technology suits their needs best.”

This, too, requires community engagement, and while that outreach is costly, so is the price of poor sanitation. Shangula told CCIJ that inadequate access to sanitation was leading to sickness and infection, while the risk of disease and pollution also threatens tourism and agricultural industries.

“There’s a need to establish what the cost of inaction is,” added Shuuya. “Perhaps the decision-makers don’t have the evidence to say, ‘This is what we’re losing out on by not investing in sanitation.’”

But while the full cost of Namibia’s crisis is unknown, it is clear the government has significant work to do to address it in a timely manner.

2022 – A couple returns home after walking a kilometer out of town to defecate in the Democratic Resettlement Community.

A weak defence

By the government’s own admission, sanitation has stalled in recent years, and the various ministries tasked with improving sanitation have each failed to prioritize the sector.

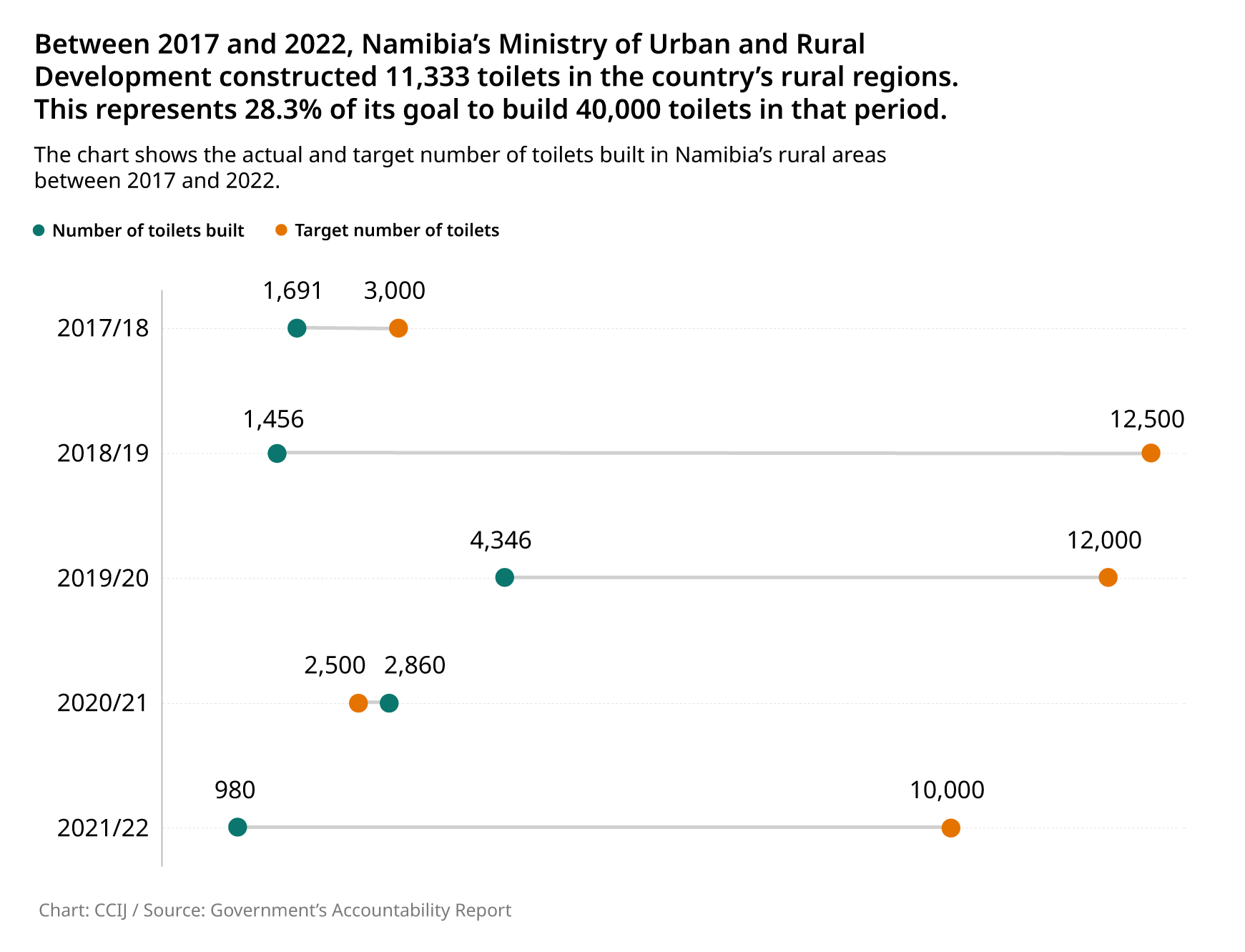

MURD, for example, has failed to hit its toilet targets in four of the last five years. In 2021, the ministry promised to construct 10,000 new toilets in rural areas but built only 980 before claiming the original target was “erroneously indicated” and that 1,000 was the real target. In explaining the failure to meet even the 1,000 toilets target, MURD said “late submission of activity plans and accountability reports from the regions result[ed] in late approval of budgets.”

The sector has also failed to communicate its strategy with members of parliament. A draft of Namibia’s 2022-2027 National Sanitation and Hygiene Policy acknowledged that one of the biggest obstacles were politicians and local authorities continuing to promise flush facilities as ministries agreed to promote dry sanitation in urban and rural areas.

And 14 years ago, the government outlined plans – with input from four ministries, local authorities and the office of the prime minister – to stimulate “behavioural change” with a national hygiene campaign. This was supposed to happen by 2015, yet Namibia has still not had a nationwide campaign to promote both sanitation and hygiene.

MAWLR, charged with the coordination of government sanitation services, admitted via email to CCIJ that challenges in improving sanitation included “poor sanitation practices and the non-involvement of communities,” but said limited access to water, resources and finance remained a hindrance.

But vast sums have been allocated to the ministries responsible for sanitation. Whether those funds are actually spent on sanitation is a matter of priority, and, in 2022, MAWLR cut its Water Supply and Sanitation Coordination budget by 72.7%.

Ngurare admitted that “most funding earmarked for water and sanitation in the last couple of years had unfortunately been redirected to the Neckartal dam,” Namibia’s largest dam that supports a large irrigation scheme in the south.

Shangula, the health minister, also blamed a lack of funds, arguing low tax revenues prevented Namibia from prioritizing sanitation. “You can only [improve sanitation] if you have money, and we don’t have enough for it,” he said. “The economic base of Namibia is very small.”

But, again, it may just be an issue of prioritization. In recent years, the lion’s share of Namibia’s health budget allocation has been spent on curative rather than preventative services, with little left for projects that could promote sanitation and hygiene.

And while Namibia may have a narrow tax base, according to the World Bank, it generates more tax revenue per capita than Botswana, Lesotho and almost as much as Zambia, three countries in southern Africa with better sanitation coverage than Namibia.

Shangula denied that other countries in the region were performing better than Namibia – with lower defecation rates and better access to sanitation – despite being presented with data that ran counter to his claim. “Botswana has a similar setup with Namibia… they are struggling with the same issues we are,” he said. “I don’t think that comparison is correct.”

While Botswana also struggles with poor informal settlements, sparsely populated rural areas, water scarcity and an arid w, according to the World Health Organization and UNICEF’s Joint Monitoring Programme, 80% of its citizens have access to at least basic sanitation, more than double that of Namibia.

Even at the highest levels of government, a lack of familiarity with the data is not uncommon. In Namibia’s preparatory meeting notes to the UN ahead of the 2023 water conference, the government claimed 46% of rural communities have access to “safely managed sanitation,” but Namibia’s own census mapping report, published in the same year, states less than 27% of Namibians in rural areas have such access. Calle Schlettwein, Namibia’s Minister for Water, Agriculture and Land Reform who attended the conference in New York, declined to comment on the discrepancy.

Eleven years ago, de Alberqueque said Namibia’s sanitation deficit was not a result of a lack of finances, but a “lack of a common vision,” “prioritization” and an “absence of effective coordination among the different ministries and between central and local government.” In 2023, these are still the biggest obstacles to improving sanitation.

But where the government has fallen short in reaching its stated sanitation goals, others are now stepping in. However, urbanization and climate change are pushing back, escalating a crisis that threatens more death, disease and contamination in the next decade.

This report was produced by the Centre for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ), a non-profit organisation that brings together investigative reporters, visual storytellers and data scientists to investigate key global issues affecting communities. This report was supported by the Pulitzer Centre.