The Morning after

On an overcast morning of August 2008, Christian Kpandei rushed off to the creeks to survey his fishing net placed all night in the river. His eyes, in memory, blisters with hope. In the past, it was common to visit the shore and find trapped slick black-headed catfishes on the net or the spiny fin of scaly tilapias.

Surprises were scarce.

Routinely, Kpandei would unstrap the cluster of fishes with a craftsman’s expertise and pull them off the net and drift home with a smile hanging on the edge of his lips. But with the Bodo crude oil spill in 2008, and a follow up spill in 2009, nothing ever remained the same, even when the people bury their suffering in pretence.

The spill experience was the defining moment in the life of Kpandei as much as the lives of about 832,000 inhabitants of Ogoni land according to the 2006 National Population Census Figure. Available data reveal that 70 % of the 15,600 Bodo people – traditionally fishers and farmers – live below poverty line and the London High Court claims that about 600,000 barrels of crude oil was spilled over many communities.

Yet, he manages to disremember the details of that day. He only remembers leaving his home hugely optimistic and returning from the water front with depressive pessimism. These were the extremes between his feelings.

His Majesty, the leader of Goi, Tomii S, Tomii, said spills were not new, neither were creek fires uncommon. He downplays any shock and recalls “the destruction of 38 fishing canoes packed in the mangrove by crude fire in the 1970s.” That notwithstanding, he concedes that 2008 and 2009 spills were “terrifying.” Christian said it was “massive.” And Dominic Saanaa, the Acting Youth Leader of Bodo, Rivers state, thinks it was “unprecedented.”

The United Nations Environmental Programme, UNEP, says that indeed oil industry operations were suspended in Ogoniland in 1993, “widespread environmental contamination remains.”

His Majesty, Tomii… The leader of Goi,

After the spills that covered the creeks, stifling, without discretion, every living thing in the coastline of many communities in Ogoni, the people initiated consultations and planned on the next line of actions. They watched the lips of the government and the body language of Shell Petroleum Development Company (Nigeria) Ltd, SDPC, whose facilities triggered the spills. Deciding the means of taking up the case was delicate for some reasons.

For one, dragging Shell to court was ideal and receiving compensation from the polluters – that’s pulling Shell into the Polluter Pays Principle, PPP – could be consoling but payments don’t heal the land; it feeds, rather trivially, the mouth in the interim. The people resolved to approach the court proceeding with two demands. One, demand compensation for damages. Two and vitally, clean up their coastline so as to restore its rich and fading vestige.

Historically, the position of most Ogoni communities, King Tomii claims, has always been on these two premises. In previous instances, receiving compensation was attainable but cleaning up was, ordinarily, far-fetched. In fact, Christian says that “Shell are more willing to pay for compensation in the issue of damages but Shell will never clean up.”

But there was change in 2009. That change was a positive change. Yet the change was not from Shell.

While the call for cleaner Ogoni land dates back to a couple of decades, the Ogoni clean up or to put it more dead-on, the government’s allegiance towards cleaning the region, was aroused by this two major spills.

Prior to the spills, mutual suspicion had grown between the company and the communities. Truce was scarce. And even in the midst of this riff, Christian thought Shell took their “inhumanity to the extreme. For seventy-two days, oil oozed like water. Flying upwards from the leaked pipes and Shell did nothing,” he says about the 2008 spills. “The second spill in 2009 lasted for seventy-eight days before Shell intervened”

The president Olusegun Obasanjo administration seemingly wanted to heal the tortured relationship between the government and the multinational oil companies and Ogoni people. The death of Ken Saro Wiwa. Unpaid compensation. But much more, the clean-up of Ogoni land, fractured the reconciliatory process and UNEP, though relatively alien to the Ogoni people, concedes that “trust” was a major undermining peace between the stakeholders in Ogoni land.

Oil-spilled land in Bodo community

Tomii measures the suffering of Ogoni in moments. He said long stories that zeroed down on the people’s fear and betrayal, and the death of Ken Saro Wiwa in 1993 was “a delicate moment of sorrow and resignation” for his people but the relief that came on June 2016 when the Ogoni clean-up was flagged off seemed “special and healing.”

The government pledged itself to two crucial task when it flagged off the Ogoni clean up mid 2016 as well as the 2009 commissioned assessment of Ogoni land; One, to investigate the level of damages done to the Ogoni or what UNEP described as “comprehensive Environmental Assessment of Ogoniland.” and “an environmental clean-up to follow, based on the assessment and subsequent planning and decisions.” The bigger task, more narrowly, was the clean-up.

The government deceived us

Accordingly, the United Nations Environmental Programme, UNEP, under government funding, in two years concluded and submitted their assessment of the impact of oil pollution in Ogoni land. With this, the first stage of the government’s bargain was delivered.

The second – remediation based on the impact of the assessment – was adjourned despite warning by UNEP that “restoring the livelihoods and well-being of future Ogoni generations is within reach but timing is vital. “Failure to begin addressing urgent public health concerns and commencing a cleanup will only exacerbate and unnecessarily prolong the Ogoni people’s suffering.”

June 2, 2016, the government of president Muhammadu Buhari flagged off, finally, the implementation of the Ogoni clean up. At the Sivibiragbara water front, popularly called Patrick’s Water front in Bodo community, Ogoni, and perhaps sensing the thick weariness in the faces of the ordinary people, the Vice-President, Prof. Yemi Osinbajo flagged off the programme with many promises.

UNEP’s Executive Director Achim Steiner, said the flag off was a “historic step toward improving the situation of the Ogoni people. He added that the scale and nature of the project means that the “clean up of Ogoniland will neither be easy nor fast, but it needs to be done.”

It was nice that Steiner placed a clause on the project. And to prove government willingness to genuinely savage the situation, the report provided a starting point. The starting point, no doubt, was the implementation of “emergency measures” detailed in the report. And when the Vice president spoke to Ogoni people during the flag-off ceremony, he calmed, wordily, frailed nerves and revealed that he knew that the “lives, socio-economic and political interest depend, to a great extent, on the quality of our environment.”

“When you hear the politicians speak, you can easily be misled into thinking that it’s from their heart to help you” says Chief Jude Baritema, the spokesperson of Bodo city, one of the largest cities in Ogoni, comprising of nearly 35 villages in Gokana Local Government Area, Rivers state. He admitted seeing rich flagging off ceremony at the waterfront but he adds equally that “nothing more than that has happened after the flag off”, and “from day one, we have never seen any sincerity from the government.”

Baritema is reserved. He is such a man that kept his voice even in moments of irk. It’s only in the redness of his eyes and the shaking of his head that his anger is laid out.

Jude Baritema…The spokesperson of Bodo city

Old Tomii wasn’t. His age and anger contradict. His fingers, raised to drive a point, was tenuously dancing in the air. But his words were clear. He took each word with elderly patience. Such that his bottled up anger, came out precise and fierce against the subject matter. “The government has deceived us” he said. “And we know Nigeria has a dead government and don’t care if we live or die. Their attitude towards the clean-up proves this.”

After months of expectations, the government pleaded that it needed more time to sort out vital issues related to the assessment report received from UNEP. It revealed that the report had flaws. Ibrahim Jibril, Minister of State for Environment, in 2017, told newsmen, that they “discovered this document was faulty to a large extent” and “had to review it.” He says this review was “the reasons we are slow.”

Kenteber Obirador, Project Officer Energy and Climate Change, Environmental Rights Action (ERA) says the minister’s comment was “shameful and pathetic.” And proves that he is more keen on “paying lip service to his master, the president. We invited UNEP in the first place because we didn’t have the technical know-how to carry out the assessment”, he says. The report, by every standard is a vital starting point, though it is not necessarily “perfect.”

Ripples Nigeria called up Kpandei for a talk on the Ogoni clean up. He was there when the trench for installing Shell’s pipe was dug 50 years ago. And he worked in that field, in what he describes as “unknowingly digging his people’s grave”. Christian pulled a black suit over a traditional old British jacket and had a blacksmith’s kind of dark glasses. He talked a little about the ongoing Bodo court case with Shell in London and Ken Saro Wiwa. And those small side talks gave way for the huge Ogoni clean up matter.

Christian Kpandei

But Kpandei didn’t talk that day. No, the term talking undermines the thick anger in his voice, and in his eyes, as he speaks. “There is nothing like clean up in Ogoni land. The Cleanup you see is only a television and radio clean up. The government is not honest! “ he summed and stayed silent.

Dangerous Delay

The Ogoni clean-up is pretty fragile. It has always had that shade of emergency. It has always had the taint of tussle. And UNEP, thoroughly, recognised this delicateness. The report revealed that the “loggerheads” between the people and politics and the oil industry created a “landscape characterized by a lack of trust, paralysis and blame, set against a worsening situation for the communities concerned.”

Upon this observation, the agency, advocated quick emergency actions to restore, partly, the lost trust and much more, the environment. The agency says that “even though the oil industry is no longer active in Ogoniland, oil spills continue to occur with alarming regularity…any delay in cleaning up an oil spill leads to oil being washed away, traversing farmland and almost always ending up in the creeks. When oil reaches the root zone, crops and other plants begin to experience stress and can die.”

Nevertheless, there are facets to the clean-up and the delay in Ogoniland especially UNEP recommendations. Ideally, the “emergency measures” in the wisdom of UNEP required radical and immediate actions. These emergency measures are eight and should have been implemented as a quick follow-up on the report. According to Fegalo Nsuke, the spokesperson of Movement for Survival of Ogoni People, MOSOP, the delay is dangerous for “many reasons.”

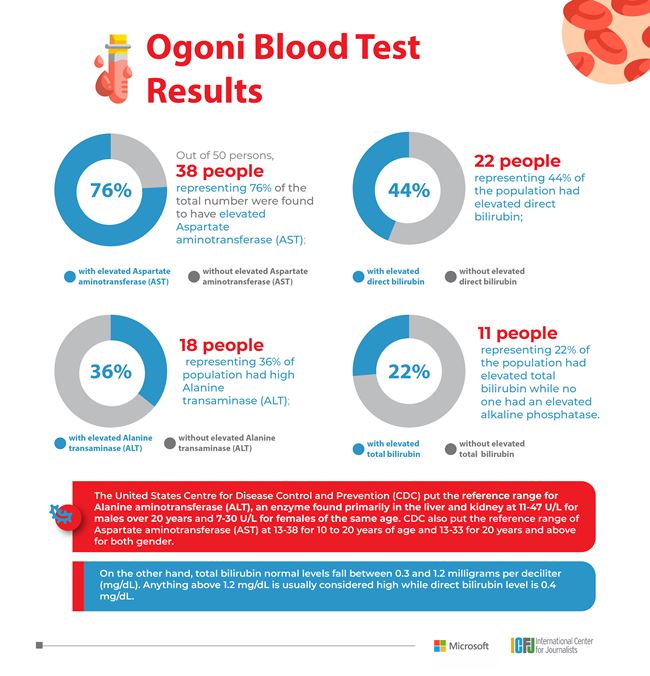

“One, the people are dying in their numbers every day. Recent community survey shows that Ogoni buries nearly forty persons weekly. This is particularly sad because majority of the diseased are young persons of between 20 – 30 or 35 years” he says.

Still, the Vice President, like other members of the government, undermined this threat. He would rather prefer that all stakeholders understand that “there is a lot going on. And that the government can’t address all of the problems at once.”

Life expectancy in Nigeria, between 2006 to 2016, increased by seven years to over 63 and 67 years for men and women respectively yet in the Niger Delta region, life expectancy, within the same period, dropped to 40 – 43 years says United Nations Environmental Programme, UNEP. This disparity, experts agree, is due to early exposure to heavily polluted environment.

There have been, ordinarily speaking, a lot of round bruising with the clean-up and the Ogoni people, in resignation, seem to be stooping below the storms. The delays, it’s been widely reported, is as a result of funding or more appropriately the controversies of funding. To trigger the clean-up exercise, UNEP, suggested an initial capital of 1 $billion dollars be set aside as part of Ogoni Restoration Fund.

In the beginning, in the days of Amina Mohammed as a Minister of Environment, she was quoted by a local media report, that “funds for the Ogoni clean-up are intact…There is no politics here. The facts are clear. The Ogoni environment has been degraded and we need to restore it. That is what we are doing.” That was August 2016.

Subsequently, the government’s New Niger Delta Vision reported that the “Vice President presided over the ceremonial signing of the Ogoni Trust Fund escrow agreement. With this signing, $170 million is to be provided imminently from the first tranche of the $1 Billion for the Ogoni clean-up that was recommended by the UNEP,” the vice president assured. That was April 2018.

Much earlier, Guardian, UK, reported that Shell was holding off the payment of their part funding for “the long delayed clean up” because nothing was in place to show that the clean-up has begun. The spokesperson of Shell said that “the money will be made avalaible when we are sure that the structures are in place, are robust and will be overseen correctly. It is very much the responsibility of the Nigerian government.” That was August 2015.

Few months forward, Shell reportedly provided $10 million dollars for the project. In a widely circulated report, SPDC General Manager, Internal Relations, Mr. Igo Weli, revealed that “SPDC JV has made available the $10 million take-off fund for HYPREP as part of its contribution towards funding its share of the Ogoni Restoration Fund.” She added that the delays in the clean-up had nothing to do with lack of funds. That was August 2017.

However, the government did not see the honesty in Shell’s position. Maybe, Shell wasn’t lying but the government was having a different view on the grounds of her probable extreme financial constrain. And when the vice president addressed the issue months later, he said that “contrary to claims that government has been docile on the issue” that the government, in the nearest future – next meeting in a week time -, would discuss “budget” for the clean-up.

“You cannot do anything without money and you cannot collect the money without budgeting for it so you have to show the work that it is meant for. We are on the right track and very soon we would all see the work being done,” he said. Osibanjo admitted, contrary to the position of Shell, that “funding was a major constraint for the seeming delay in the project and the clean-up exercise.” That was November, 2017.

Prior to the government’s self-satisfying position, the Governor of River state, Nyesom Wike says the government was not serious with the clean-up. He told the Senate Committee on Environment led by Senator Oluremi Tinubu that the “The federal government is not serious about clean-up of Ogoni land. We are tired of telling our people that the project would start next year. Let it not be a political project. Look at the North East, a commission was established and $1 billion dollars was released.”

Probably touched by the agitations raised by Wike, Chairman of Senate Committee on Environment, Senator Tinubu, imminently, articulated a new line of action. “We are concerned about the issues, “she started. “We will use face masks when we get to the location. Face mask would draw attention of the message to the world on the essence of the clean-up”.

Fegalo of MOSOP said “It’s difficult to trust the Nigerian government on this. They have not kept their words at all. In seven years, the government has not been able to provide water for a single person in Ogoni land. The standards recommended by United has been flawed. In the end, this clean up would not result in a clean Ogoni land”.

In all these, Ibrahim Jibril, the Minister of State for Environment, feels that the “rush” to clean up Ogoni was needless. Seven years and counting, he thinks, is a short time to implement at least the emergency measures. The clean-up, in his view, could harmlessly take a longer time. His tone suggested that the people, after all, have been on their suffering for years.

He says that “accusers” should know he is not in a haste to fail.

“You may say we are slow, yes we are slow and these are the reasons we are slow and the accusers who say we are doing it for politics and now that we have won, that is why we are not doing anything again. For so many years, these things have been going on and nothing happened and now that we are on the verge of doing something, everybody is impatient” he stated.

Quite honestly, the minister was on point. The government have done nothing. For the past three years they are still on the “verge of doing something.”

Again Kentebe, an environmental activist, feels this is sad. The fact that the people have been on this suffering for decades should make the government sympathetic and humanly quick. The government should understand that cleaning up ogoni land is not a gift to the people, it’s their right irrespective of the number of past administrations that had skipped that task, he argues.

One of many polluted lakes in Ogoniland

UNEP, foresightedly, warned that delays could escalate the magnitude of the damages done to the Ogoni land and in some ways emphasized this view lightly when it indicated that “while no oil production has taken place in Ogoni land since 1993, the facilities themselves have never been decommissioned. Consequently, the infrastructure has gradually deteriorated, through exposure to natural processes, but also as a result of criminal damage, causing further pollution and exacerbating the environmental footprint.”

This delay has consequences, Amnesty reported in 2018. It shows that the government has taken only limited steps to do things rightly and ordinary people keep paying the prize. But beyond rights, Fegalo, the spokesperson of MOSOP says that the government is “provoking Ogoni people to violence but the people have remained peaceful.” And the government is creating the impression that “only violence is rewarded.”

“The government would be happy if we take up arms so that they can wipe all of us out in one day like they killed over 4000 indigenes of Ogoni when we stood up for our rights between 1993 -1999” he said.

HYPREP Has Failed

Kpandei who said he was trained by three British masters, lamented, “There is a lot of propaganda on the radio and television that a clean-up is taking place in Ogoni land but when you go to the site or communities, look into the creeks, make your research and find out from the people, you would know whether the reports on the media are true or not,” he revealed.

Sadly, Kpandei was saying this in low spirit. His voice was clear and fragile but his face was far too troubled.

To understand the context of Christian’s complains or contempt, the suggested modalities for the exercise would be revisited. The Hydrocarbon Remediation Project, HYPREP, was established to implement the recommendations of the UN Environmental Programme report. The task of HYPREB, experts say, was pretty clear. Even if the UNEP report was, in some instances, imperfect, only few adjustment would be required. Much more, the roles of HYPREP was divided into phases.

First off, HYPREP primarily ought to start the implementation of the reports from the emergency measures. To skip this modality would have consequences. And this consequences would be ugly. The report argues that those recommendations were structurally interconnected such that altering the steps or side-lining some would undermine the progressive success of other stages and of courses, the entire process.

The United Nations Environmental Programme says the document provided the “foundation upon which action (can be) undertaken to remedy the multiple health, environmental and sustainable development issues facing millions of people in Ogoni land,” adding that the report “can provide a firm foundation upon which all the stakeholders concerned can, if they so wish”

Whichever way, the starting point was to imminently execute the emergency measures. The emergency measures were eight and vital and fragile. The UN agency said that these measures “warrant immediate action.”

Generally speaking, a health audit of the entire region was suggested, in addition to providing adequate drinking water for impacted sites plus initiating a survey of all drinking water where hydrocarbons were observed. These three, alongside health awareness campaign deterring communities from neither engaging in artisan refining or living in communities having contamination exceeding intervention values and warning families not to drink, swim and bathe or walk in place and rivers where hydrocarbons were observed in the surface.

“When HYPREP asked us to leave our homes and livelihoods, they gave us nothing. Our people are aliens in different places and many people have died. I may not be alive to see Ogoni clean but the government should heal our land for those who would survive” Tomii said.

With those words, Tomii went silent.

Abandoned house….. The people were sent away from their houses without any support

Observers, from the duty of care point of view, argue that HYPREP had no reason sending people away from their lands without any support to resettle away from their livelihood. And till today, communities within Ogoni land still drink contaminated water because “HYPREB did not provide a single well for us here” says Fynface, The Executive Director of Youths and Environmental Advocacy Centre.

But there are other reasons, more narrowly, to which the failure of the HYPREP has been ascribed. The discriminatory isolation of select communities in Ogoni land from the exercise; creating more troubles than it rolled away according to local sources. For instance, Bodo, one of the largest and most polluted communities in Ogoni land has been isolated from the faulted, medical outreach. And has in fact “lost touch with the clean-up” according to Baritema, the spokesperson of thirty-five village Bodo.

Kpandei says “the average man doesn’t know anything about what HYPREP is doing. The agency doesn’t have the charisma to carry out this clean up. They have failed. HYPREP has lost their credibility. The people in HYPREP have no vision, they have no focus.”

Swamped by this round bruising, HYPREP, rather shockingly, has no reason to panic. The government, whose tone it must dance to is pretty pleased with its job. The president, Muhammadu Buhari, speaking in the three years of his administration said that “the environmental clean-up of the region (Ogoni land) is progressing satisfactorily.”

The government too, to put it bluntly, must have been impressed, or better still, seduced by the aired efforts on television or radio most times in respect to the clean up. After all, the president has never been to Ogoni land in his administration. He has never seen the oil upon their waters. He has never seen their crude sailing on their soup or the dark boundless sheet of soot on their waters or the dark overcast over them at twilight. And when the rare opening of launching the clean up in 2016 came by, he was pleased to pass on it.

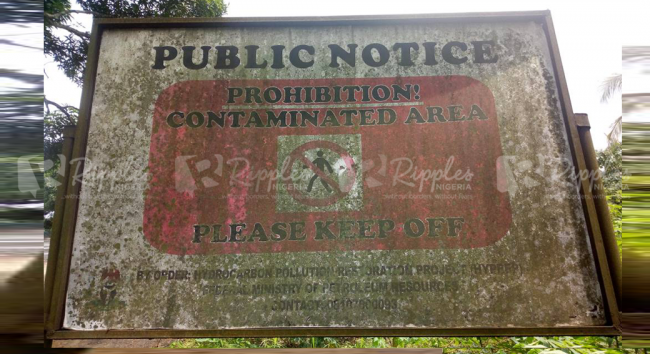

A rusty sign-post prohibiting movement due to contamination

When Ripples Nigeria reached out to Dr, Marvin Dekil, the Project Coordinator of HYPREB, he was courteous at first, but as soon as our correspondent introduced himself, and the reason for the call, that it has to do with the Ogoni clean-up, his demeanour changed, and everything turned from unassuming courtesy to subversive antagonism.

“You can’t talk to me just like that. There is a due process. In fact, I am in a crucial meeting. And if you want to talk to me, go to the website and apply for the opportunity” he hollered and hung up.

A trusted source close to Dr. Marvin offered some explanation for his attitude. He pleaded that we ought to empathise with him. “Everybody is beginning to find out that he is doing nothing. It has been frustrating for him and it is difficult facing one media organisation after another. With all these reports, he feels the government may axe him”.

The source suggested that the presidency could have been misled into believing that the clean-up was working. His view is not an outcast. And didn’t differ in perspective from Fegalo’s who revealed that “a lot of propaganda was going into the clean-up.”

Based on Marvin’s assertion, our correspondent sent an email HYPREP, aligning with his expectations towards “due process,” and indicating that the request was urgent, relatively.

Seven days later, there was no reply. A friendly follow-up was sent across. After another seven days passed with still no feedback, our correspondent again called Dr. Marvin. Several call to his number went unanswered.

“To have said that cleanup was progressing satisfactory, for us is something that came very surprisingly,” Conflict Adviser of CISLAC, Mr. Salaudeen Musa, said at the meeting of civil societies in Port Harcourt late May. “Tendencies are there that the Advisers of the President are not advising him properly. Tendencies are there that they are feeding the president very wrong information.”

Beyond the inadequacies of the present efforts, locals accuse HYPREP of deliberately running an isolative and selective clean up, ignoring many deeply affected communities in the process.

The spokesperson of Bodo, Baritema says “HYPREP doesn’t have program, it has never had and it’s better scrapped. Bodo is one of the largest community affected by the spills in the Niger delta.” He continued, “but we have been completely isolated from the clean-up exercise.”

A polluted river

But he has no regret because, according to him, his people “don’t need a jamboree health outreach where people would be fighting for paracetamol and multivitamins and mosquito nets. HYPREP picked better grounds where they can be worshiped and fool the people and sell their lies. My people are wise.”

If Ken Wasn’t Killed

Seeing the situation of the people, and the strength of the pollution, it’s natural to feel terrified and provoked. One remembers the words of the elders, many of whom may die before another visit to Ogoni, many of whom may go blind too. One remembers the sick bones of weighed souls wearing wizened skins, the black spring and the thick dark waters. And it’s not easy to forget, the slow tear coming down the cheek of Tomii when he said his own death could be few months away.

Needless to say, the distress of the people, as well as the suffering of the widows of pollution, and the legion of early deaths recorded weekly, is as vivid as the sun rising from the neon-yellow cloud during the first visit to Ogoni.

“If Ken wasn’t killed,” Tomii said, “we would have been saved.”

Tomii stayed silent now. He was facing his own portrait, taken probably in his thirties, his broad chest pushed forward, and his face vacant. There is such anguish in that silence, one could easily commune with his people’s suffering.

Maybe Ogoni land and the rest of Niger Delta deserve more. Maybe Nigeria has been unkind in the past. Maybe, it’s time to heal their land and water. Maybe, it’s time to set Tomii free from his despair. Maybe, it’s time to calm the rage of this people.

This story is supported by Ripples Centre for Data and Investigative Journalism.

RipplesNigeria… without borders, without fears

Click here to join the Ripples Nigeria WhatsApp group for latest updates.