On June 11, a Trans-Niger Pipeline operated by Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) of Nigeria Limited burst open, spilling crude oil into the environment in Aleto, a community in Eleme Local government in Rivers State. The spill also contaminated Okulu River, the only source of drinking water for five communities, threatening residents’ health and affected farms. Arinze Chijioke was in Aleto to capture the level of impact.

A typical day in Aleto and other surrounding communities in Eleme, which occupies the Western end of Ogoniland land in Rivers state, begins with residents working on their farmlands and young men casting their nets into the Okulu River.

Farming and fishing have been the predominant sources of livelihood for residents of these communities for decades. The river-which extends to over five communities, is always a beehive of activities.

Families living along its banks always come out to relax in the evening hours. Apart from fishing, residents of the communities also drink from the river.

But that was just before a Trans-Niger Pipeline operated by Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) of Nigeria Limited, operator of the NNPC/SPDC/Total Energies/NAOC Joint Venture burst open, spilling oil into the environment and the Okulu River.

The point from where the spill started

Now, nobody gets close to the river; it is almost like a ghost town. Many households living close to the river are relocating to avoid the health risks arising from inhaling crude. Some residents have fallen sick as a result. Fishermen have lost their livelihoods. Crops damaged.

In 1993, Shell ceased active exploration and production in the areas covered by Oil Mining License 11, following the unresolved issues between the government and the host communities of Ogoni, which fuelled resistance and restiveness among the people. The Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), led by environmental rights activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa organised protests of around 300,000 Ogoni people against the company.

However, pipelines are still active, including the Trans-Niger Pipeline (TNP), which traverses Ogoniland and is used to transport crude from oil fields in other areas through the communities to export terminals.

As it happened

It was on a Sunday morning in June, Gomba Oluka, a resident, recalled. He had woken up and perceived the smell of crude, and when he came out, he saw that the river was gradually being covered by oil sheens, dead fishes, and other sea creatures mired in sticky crude.

“I could not draw close because of the heat. My eyes started hurting me,” he said. “I returned home and thought we could manage, but it became worse, and my wife and children could not breath well”.

Oluka says the spill impacted on his farmland

The next day, Oluka and his family escaped to Aleto town, where they spent three weeks.

“By the time we returned, my sources of livelihood were gone because I fish and feed from the river, “a distraught Oluka said. “My cassava and plantain farms close to the river have also been damaged as a result of the spill, even the economic trees”.

At least five communities through which the river runs, including Aleto, Ogale, Agbonchia, Onne and Akpajo have been impacted as a result of the spill and more than a month (since June) after the incident occurred, the acrid smell of crude is still fresh in the air, the water surfaces still covered by oil sheens.

Till now, the volume of oil spills has not been determined. Communities’ members say this is not the first time Aleto is experiencing an oil spill. However, it is the biggest in terms of impact.

An environmentalist whose non-profit, Youths and Environmental Advocacy Centre, (YEAC Nigeria), monitors spills in the Delta region, Fyneface Dumnamene described it as the worse in Ogoniland in the last 16 years after the 2007 crude oil spill in Bodo community.

“Nobody from the company has come to find out how we are surviving following the spill,” Oluka the fisherman said. “I now buy bags of water because our water source is gone, and our boreholes are not even working due to years of exploration. I also buy Fish, all of these things we used to have,”.

Nobody has accepted responsibility for the latest spill. But community members say its equipment failure as the pipeline is hardly maintained or renewed by the company. Every year, several hundred oil spills are recorded in Nigeria, causing significant harm to the environment and putting human lives at risk, but oil companies operating in the region often blame pipeline vandalism by oil thieves or aggrieved young people in affected communities for spills, which could allow the companies to avoid liability.

While there are currently no legally binding regulatory penalties or fines for oil spills in Nigeria, the oil company whose facilities have been compromised are always responsible for the clean-up, regardless of the cause. The company is also required (by law) to close off/stop the spill within 24 hours of being notified of an oil spill in its jurisdiction.

Working to prevent spills?

On its website, the Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) claims that it demonstrates a commitment to improving the quality of life for all those who live and work in the Niger Delta by listening and responding to issues and concerns of host communities of the joint venture operations and facilities and cleaning up all spills from its facilities, irrespective of the cause.

It also claims that it continues to undertake initiatives to prevent and minimise spills caused by theft and sabotage of its facilities in the Niger Delta. In 2017, it reported sustained on-ground surveillance efforts on SPDC JV’s areas of operations, including its pipeline network, to prevent incidences of third-party interference and ensure that spills are detected and responded to as quickly as possible.

“We continue to sustain our regime of daily over-flights of the pipeline network areas to identify any new spill incidents or activities,” it said. “We have also installed state-of-the-art high-definition cameras to a specialised helicopter that greatly improves the surveillance of our assets and have implemented anti-theft protection mechanisms on key infrastructure”.

But an environmental activist, Johnson Frank, told The ICIR that while the company tried to stop the spill days after it occurred, no clean-up has been undertaken so far.

“We are really angry because the spill has cost the community a lot, and the environment has been damaged,”.

Shell spokesperson Michael Adande said that the Joint Venture and other stakeholders have commenced an investigation to unravel the cause of the incident.

However, Frank does not think any ongoing investigation or negotiation is yielding results because the spills are still visible more than a month later. He says it shows a high level of irresponsibility and disregard for the people and their environment by the company.

“What is most worrying is that the company has not provided water for the people, and they are destroying the one we are using to survive, “he said. “They are only exploiting us and do not have regard for our wellbeing.”.

Health threatened

Martha Egbe, a resident of the community, has been stooling and vomiting ever since she ate a fish she bought from the local market to prepare soup for her family.

“After using it to cook, I felt crude in the soup and had to pour everything away, “But it had already got into my system and destabilised me, “she recalled. “Now, I am taking some drugs so I can regain my health”.

Egbe, who also suffered shortness of breath, lost her Cassava farm as a result of the spill. She said that the community has recorded several illnesses and even deaths in the past due to oil spills.

“When I dig the ground, I discover that my Cassava tubers are rotten. It is the same thing for households who have farmlands close to the river”, said Egbe, who was part of those who protested, demanding immediate action from the company.

Crude on debris from the river

She spoke of how she noticed the spill that Sunday morning on her way to Port Harcourt for a meeting and quickly called some young men in the community who mobilised to the location where the pipeline burst open.

“Now, our young men are without jobs because their source of livelihood, which is fishing, has been destroyed.

“We cannot even go to our farms again because there is nothing to harvest” she explained.

Joy Sunday owns mini provisions store close to the river, and her customers are usually those who come to relax and others who used to sell fish caught from the river.

“That is what I have been using to survive and train my children. But the spill has sent many of them away from the community, and that is affecting my income. Some days, I don’t make sales” Sunday told The ICIR.

Ogoni, a land still waiting for clean up

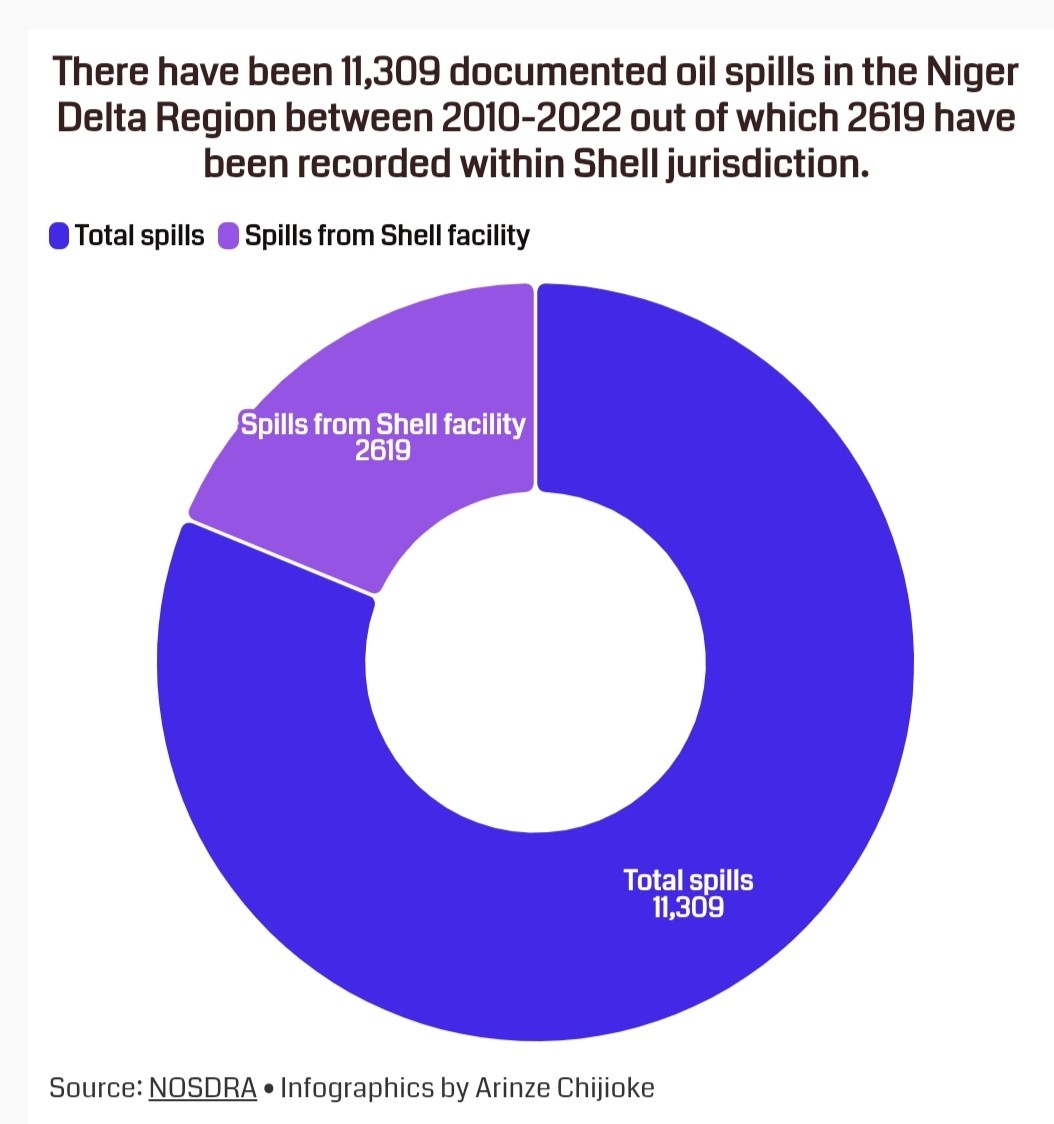

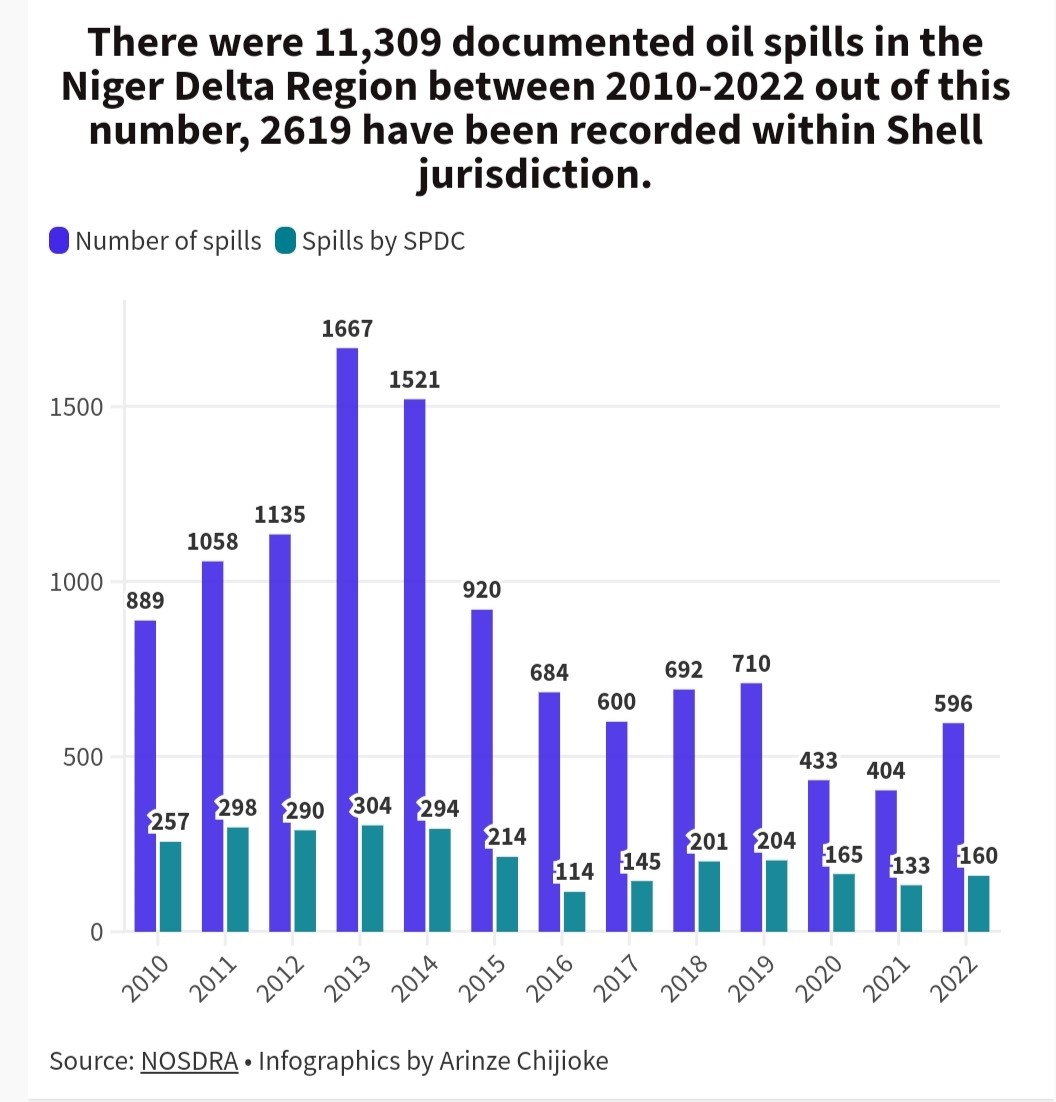

Since 2010, there have been 11,309 documented oil spills in the Niger Delta Region. Out of this number, 2619 have been recorded within Shell’s jurisdiction, according to data from the website of the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA).

In 2022, the agency recorded a total of 596 oil spills, resulting in 18,855 barrels spewing into the environment. Shell alone had 160 spills and 1186 barrels.

In 2006, the Nigerian government commissioned the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to conduct an environmental assessment of Ogoniland, the epicentre of spills with over 261 communities. Its report released in 2011 criticised Shell and the Nigerian government for 50 years of pollution, recommending the creation of a USD 1 billion Environmental Restoration Fund for clean-up.

The government announced a clean-up in 2016 after the relaunch of the Hydrocarbon Pollution Restoration Project (HYPREP). But activists like Morris Alagoa, head of field operations, Environmental Rights Action/Friends of Earth Nigeria (ERA/FoEN), say that both clean-up and remediation have been very slow.

In 2020, an international coalition of civil society organisations (CSO) consisting of Amnesty International, ERA/FoEN Europe and Milieudefensie/Friends of the Earth Netherlands released a report detailing the extent to which the government and the Anglo-Dutch oil giant have implemented UNEP’s recommendations.

Titled No Clean-Up, No Justice: An Evaluation of the Implementation of UNEP’s environmental assessment of Ogoniland, nine years on, the report also confirmed that progress has been slow, lacking transparency and accountability as HYPREP has only focused on a fraction of the total area-67 sites, covering a surface area of 943 hectares-identified by UNEP as needing clean-up and remediation, with only a few sites appearing to follow the required remediation procedures.

This is even when the Ogoni Trust Fund received the first payment of US$10 million from the oil industry in 2017 and further payments in 2018 and 2019, bringing the total to US$360 million.

Alagoa adds that the community entry issues and stakeholders’ disagreements also affect the pace of work in Ogoni. He said there were distrust and misunderstanding regarding the scope of work and what needed to be done.

“Some community stakeholders were seeking explanations, especially as to how it affected their communities,” he said. “They were either trying to ensure they were not shortchanged or for their benefits as per the entire project”.

The programme manager, Portharcourt Office of ERA/FoEN, Kentebe Ebiaridor says that the latest spill has a significant impact on the ongoing clean-up efforts in Ogoniland because there ought to be a decommissioning which is the strategic approach to deactivating a project or facility from service as required by the UNEP report while the clean-up is ongoing.

“Sadly, they have boycotted that process, and that is why we have spill almost every week in the region, which continues to increase the poverty rate of the people and reduce the economy of the communities and also threaten their health”.

Ebiaridor said that the Nigerian government must start thinking about alternative sources of income and energy outside of oil which should remain in the soil, especially since it has impacted lands, water, air and livelihoods.

NOSDRA accused of deliberately delaying report of the spill

Members of the affected communities and environmental activists are accusing the NOSDRA of deliberately refusing to conclude and release its Joint Investigative Visit (JIV) report from the community more than a month ago.

On its website, the agency states that a JIV must (by law) be carried out as soon as possible after a spill has been identified and containment measures are taken. The JIV involves oil company representatives, community representatives, and appropriate government agencies visiting the oil spill site to agree on the spill’s cause, impact and scale.

After the visit, the resulting JIV document is signed by all parties present and forms the basis of any legal proceedings or compensation claims. But it has been more than a month since the spill was reported. Yet, NOSDRA has not concluded its JIV.

The Trans-Niger Pipeline

When contacted, Zonal Director of NOSDRA, Ime Ekanem said, “We are yet to conclude the JIV, as at Friday, July 14 and Saturday, July 15, what we were doing was the delineation and mapping of the impact areas”.

Reacting, Fyneface of the YEAC said that NOSDRA’s prolonged silence on the oil spill calls to question the agency’s capacity to still be trusted with the responsibility of oil spill detecting and response.

“It is worrisome and unacceptable that till now, NOSDRA has not been able to synergise with community people, Shell and other stakeholders and agree on the cause of the devastating crude oil spill in Eleme,” he told The ICIR.

He also said that the Eleme spill portends what is to come for host communities in the Niger Delta because obsolete pipelines would continue to burst and spill crude into the environment. This, according to him, is despite the coming into force of the Petroleum Industry Act (2021).

“The Indigenous companies buying the divested facilities of the International Oil Companies are inheriting liabilities with meagre resources, technology and manpower to manage the facilities and address incidences of oil spills when they occur,” he said.

Shell refuses to react to spill

In order to get Shell to respond to questions regarding the spill, this reporter contacted three workers at the company, including Osilaollor Dabor, Sunny Abuede and Babalola Akinpelumi. But all of them refused to speak on the matter, insisting that they were not in the position to respond.

However, Shell’s spokesperson, Adande was quoted as saying that they were working closely with a multi-stakeholder Joint Investigation Visit team led by NOSDRA, in collaboration with Rivers State Ministry of Environment and community representatives, as the investigation into the cause and impact of the incident progresses.