In the second of this three-part series, Arinze Chijioke was in communities most impacted by the 2022 flooding in Delta State to document the pains and losses of the people and how they are struggling to survive. He also looks at how the state government is failing to provide a solution to the challenge.

Ebimode Ebowm was in his family house in Odoburu, a community in Patani Local government in Delta State when the flood began exactly a year ago (in August 2022). But because he could not walk, he stayed indoors, on top of his bed and watched as the water level increased.

Soon, the water found its way into the house, a one-room thatched building, constructed with mud and held together by bamboo. The room was gradually being covered; his bed was soaked in water. Still, he remained indoors.

“I was helpless and cried every night for over two months, “recalled Ebowm. “Me and my family could not move to the roadside like others were doing,”.

Ebowm caught a fever because of exposure to cold. He was vomiting, peeing and pooping in the same spot. He could not visit any hospital and had to depend on herbs to get back to normal.

Ebimode Ebowm could not run when the flood came

New Year, Ebowm’s father said that the flood went away with household items and also destroyed foodstuffs. He said it destroyed his Cassava, Pepper and Potato farmlands which were completely submerged.

“We started begging for foodstuff from neighbours who still had some to spare, the water level got to my waist,” said New Year. I stayed in my room with my seven children till the water dried up,”.

His wife, Finere had to go fishing to fend for the family.

Ebowm’s family is only one out of hundreds of households in Odoburu whose livelihoods were destroyed, following the 2022 flooding in Delta state. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), at least 78,640 individuals in 12,070 households in Delta State, were affected In the aftermath of the flooding seven local governments accessed.

Ebimode’s family house after the flooding

Since 2012, flooding has been a usual occurrence in Odoburu and other lowland communities which lie on the bank of the river Niger, making it easy for farmlands and houses to be completely submerged. Before 2012, it was not common but as the intensity of water increased, it became easy for the houses to be submerged.

Worse in a decade

The 2022 flooding was the worst in a decade, with 662 people reported to have lost their lives while over 2 million were displaced. A report by the World Weather Attribution showed that it occurred as a consequence of above-average rainfall throughout the 2022 rainy season exacerbated by shorter spikes of very heavy rain leading to flash floods as well as riverine floods and the release of the Lagdo Dam in Cameroon.

New Year, Ebowm’s father

“The devastating impacts were further exacerbated by the proximity of human settlements, infrastructure (homes, buildings, bridges), and agricultural land to flood plains, underlying vulnerabilities driven by high poverty rates and socioeconomic factors (e.g., gender, age, income, and education), and ongoing political and economic instability,” the report found.

Nigeria’s Minister of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development, Hajiya Sadiya Umar Farouk said that the country lost between US$3.79 billion to US$9.12 billion in economic damage due to the flooding.

Sleeping by the roadside became the only option.

Ebiere Bunu lost her Cassava, Pepper and Plantain farm to the flood which also affected her house. She, her husband and five children constructed a makeshift tent covered with mosquito nets by the roadside where they spent the whole of September and October.

“When it started coming in at first, we raised our beds and other household items. But it soon became serious and crossed window level and we escaped to the main road. My big foam spoilt and we had to squeeze ourselves into one,”.

For Bunu’s family, feeding was not much of a problem at the time because she brought out some Cassava before the water completely took over her house. But her clothes and other property in the house were all gone.

Ebiere Bunu lost her entire farmland to the flooding

Apart from Odoburu, communities in Bomadi, another local government were also submerged by the flooding. Sadly, in the entire period the flood lasted, there was no form of intervention by the government, whether state or federal.

A resident of Bomadi, Fufeyin Zachariah said that In the entire LG for instance, only three bags of Rice came in as palliative from the government. In Kpakiama community, individuals contributed about 7 bags of Rice which were shared and households got 3 cups each.

“It was a mockery on the people who had lost everything they had to flood, “he said. “Apart from the main town, other communities in the LG were submerged by the floods,”. Most of the houses constructed are with mud and thatch and that makes it easy for the rains to wash them away.

He explained that the challenge of flooding in Odoburu and other flood-prone communities is partly a structural issue because most houses are built under the road level and that makes it easy for water to flow into people’s homes.

The flooding surpased the window level at Bunu’s house

“But these days, people are beginning to raise the levels and it requires a lot of sand filling to get the level where water cannot penetrate, “he said.

Massive hunger

As soon as Lucky Rachael, a resident of Kpakiama Community noticed the rain entering her house gradually, she packed some of her things and went to a secondary school in her community.

The flood destroyed the farmland where she planted Cassava and over 500 Yam tubers and plantain. It destroyed her house too. At the school, where other residents of the community found refuge, Rachael said they always saw snakes.

“Yet, some households were managing till it was submerged too,”. “I escaped to my grandmother’s house with my husband and children,”.

Where Bunu and her family slept while the flood lasted

During that entire period, Rachael and her husband always stayed up at night, thinking of how to start rebuilding her life again. They barely fed daily because there was nothing to eat. Now, she sells Rice in her community while her husband moulds blocks so they can feed. They are rebuilding their house again.

All the farms in Kpakiama and Odorubu communities were swallowed up by the floods and that meant that farmers had to buy food items- like Garri and Rice-which more than doubled in price. As a result, there was widespread hunger because many households could not afford the amounts. Some of them went for days without food, except when NGOs came around to distribute packs.

The traditional ruler of Kpakiama community, HRH. Bunu Abakederimo said that the 2022 flooding cost his people a lot of their fortune. He said that most households are still trying to recover from the devastating impact of the incident.

Traditional ruler of Odoburu, Bunu Abakederimo

He regretted that till now, residents of the community have yet to receive any form of help from the government to help cushion the effect of the flooding on them. This is even after the release of billions of naira by the federal government.

“We only heard on the radio that the government was bringing relief items, but we have not seen anything,” said Abakederimo. “Now, we are beginning to experience the rains again and we don’t know what will become of our houses and farmlands,”.

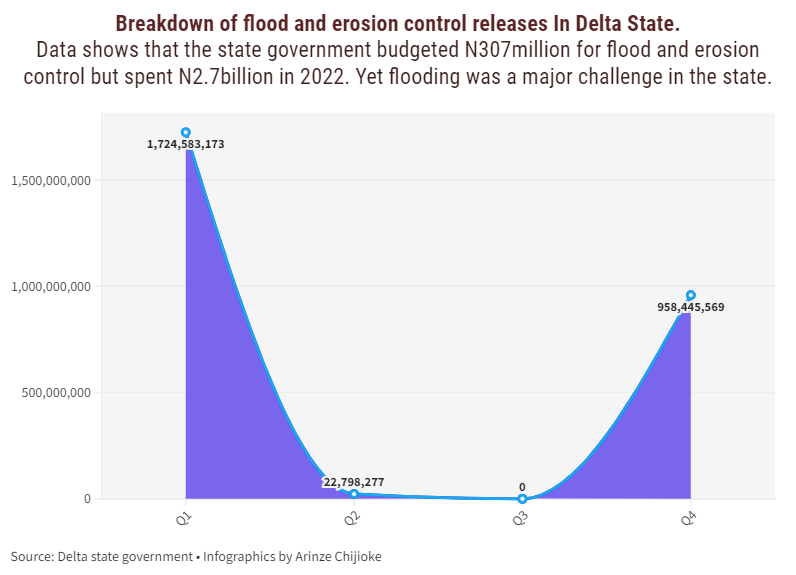

A review of the 2022 budget for Delta shows that the state government spent more than its budget for flood and erosion control, yet, it was a major challenge in the state. Out of N307 million (307,700,000.0) budgeted, the government spent N1.7 billion (1,724,583,173.16) in the first quarter, N22 million (22,798,277) in the second quarter, no amount for the third quarter and N958 million (958,445,569.15) in the fourth quarter, taking the total amount spent to 2,705,827,019.81 and surpassing the original budget with N2.3 billion (2,398,127,019.81).

Between 2021 and 2022, the state government received a total of N1.4 billion as its share of the ecological fund. In January 2023, it was given another N123.2 million. Yet, floods wreaked havoc across communities. Out of N305 million (305,700,000) budgeted for flood and erosion control in 2023, N177.9 million (177,935,075) has already been released in the first quarter.

Disease outbreaks

While there is no data on the number of deaths following the flood, residents say sicknesses such as Cholera, malaria Typhoid and other water-born diseases increased. The rivers were contaminated, yet the people drank from them as they had no other option.

“They bathe and poo inside the same water they drink, said Zachariah. “What is most worrying is that our hospitals are bad, with no workers. In the health centres, there are no drugs and so, many people had to rely on local herbs throughout the duration of the flood,”.

Both the International Rescue Committee IRC and UNICEF reported that cases of diarrhoea and water-borne diseases, respiratory infection and skin diseases rose, following the 2022 flooding.

UNICEF’s Children’s Climate Risk Index (CCRI) launched in August 2021 showed that Nigeria ranked second out of 163 countries considered at ‘extremely high risk’ of the impacts of climate change.

Lucky Rachael escaped to her mother’s house following the flooding

The CCRI is the first comprehensive analysis of climate risk from a child’s perspective which ranks countries based on children’s exposure to multiple climate and environmental shocks combined with high levels of underlying child vulnerability, due to inadequate essential services, such as water and sanitation, healthcare and education.

Titled the Climate Crisis Is a Child Rights Crisis: Introducing the Children’s Climate Risk Index, the report found that Nigerian children are highly exposed to air pollution and coastal floods.

It however suggested that investments in social services, particularly child health, nutrition and education can make a significant difference in our ability to safeguard their futures from the impacts of climate change.

Extinction just by the corner

Catholic Bishop of Bomadi, Most Rev. Hyacinth Egbebo said that communities in Bomadi and other locations that are prone to flooding will go into extinction if nothing is done to deal with the perennial flooding issue.

“People will be forced to migrate because it has become a yearly occurrence, he said. “It makes life difficult because water bodies are polluted, even the gas that is being emitted by oil companies comes down as acid rain and with no other option residents drink all kinds of contaminated water,”.

Catholic Bishop of Bomadi says extinction just by the corner

He explained that Bomadi town is usually not badly affected because there are roads which stand against the water finding its way into people’s homes, adding that the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), which should provide some of the roads across communities is non-existent.

According to him, the way out will be for the government to expedite action in the construction of a dam that will receive water each time it is released from Cameroon and also dredge the river Niger which usually overflows its banks.

In Kpakiama and other communities, residents are already bracing up for another flooding season. They are harvesting their Potato, Cassava and other crops prematurely for fear that they might be destroyed by flooding. Usually, it takes six months after planting before harvesting starts, but in May, the fifth month of this year, the rains came down and crops were being affected, hence the decision to start harvesting early. They planted early too.

The National Emergency Management Agency has already warned residents in flood-prone areas/ states, including Delta to relocate, following the expected release of the dam. Even the state government has warned residents in low-land and flood-prone areas to relocate to higher planes due to expected floods from the release of water from Cameroon’s Lagdo Dam into the Rivers Niger and Benue.

“The Delta State Government will provide support to those displaced from their homes by the rising water level occasioned by the overflow of the River Benue and River Niger,” the Chief Press Secretary to the State Governor, Festus Ahon was quoted as saying in a statement.

In a letter dated August 21, 2023, the High Commission of Cameroon wrote to the Federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs as regards the opening of the dam. However, the Director-General of the Nigeria Hydrological Services Agency, Clement Nze, noted that the dam had been releasing water even before the letter was sent to Nigeria by Cameroon.

With no alternative residents of Odoburu and Kpakiama still drink from the conterminated river

“I got in contact with the manager of the dam and he confirmed that they opened the dam on August 14, 2023, at 10.10 a.m., Nze said. “He said they had been spilling water at the rate of 200 cubic metres per second, which is about 20 million cubic meters per day,”.

Way forward

Flood risk expert, Taiwo Ogunwumi said that the government needs to develop a sustainable drainage system and also improve flood early warning communication by adopting all media outlets including Radio, community campaigns, schools, farmers’ groups, women’s groups and TV.

He also said that the government needs to initiate a mangrove restoration program, most especially the planting of trees along the shoreline of the major cities (Delta, Lagos and Kogi State) and other riverine communities as mangrove has the capability to retain water.

“Cameroon will continue to release water from the Lagdo Dam, hence The Nigeria government must expedite efforts in completing the dam project and work towards building more to save the country from riverine flood disaster,”.