In 2022, Nigeria faced devastating floods, it was the most destructive the country has experienced in a decade. Infrastructures, crops, and houses were damaged, leading to decimated livelihoods and the displacement of several households. This report examines how humanitarian initiatives helped victims rebuild their lives in Kogi State.

Friday Egwuma, a resident of Onyedega, one of the communities of Ibaji town in Kogi State and his family had gone to bed when he noticed water gradually flowing through the main entrance door, into his living room. It was past 9 PM on September 15th 2022.

“Quickly, I came out and started removing some of my property,” he recalled. “That night, I and my wife arranged chairs and placed a mattress on top of it, so our children could sleep,”. “I stayed awake till dawn,”.

“The next morning, the water increased and my house became uninhabitable,”. “I took some of my things to an upstairs apartment belonging to the traditional ruler of the community and begged him to allow me to pack them there and also stay with my family, he agreed,”.

An Enumerator, Hope Akwu registering a beneficiary at Onyedega

Other members of the community were also accommodated in the apartment.

In the aftermath of the flooding, Friday lost his Rice and Yam cultivation to the flood disaster. He had planted 12 basins of Rice and 3000 Tubers of Yam, hoping for a bountiful harvest.

“Soon, it became difficult for me to feed my family, we spent two months living outside our own house, “he said. “Although the community leader brought food, it was hard enough because of the crowd,”.

“As days passed and help did not come from anywhere, including the government that promised to support families affected by the floods, I gave up hope and resigned to fate, sometimes, we slept without eating, “Egwuma further explained.

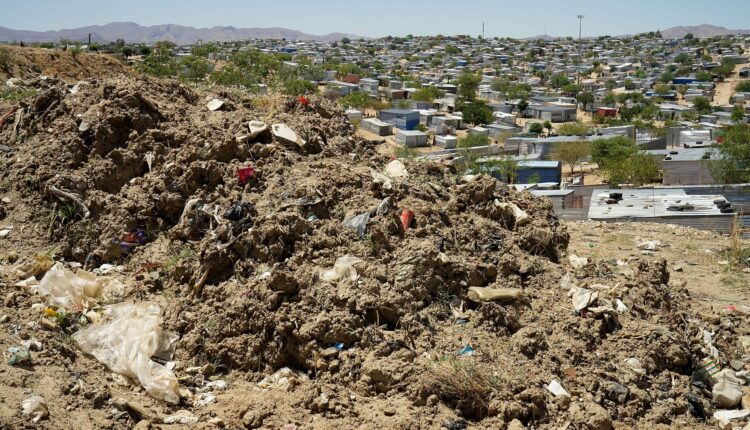

Onyedema was one of the worst-hit Nigerian communities after the river Niger overflowed its banks, flooding houses and farmlands last year. Climate variability and the release of excess water from the Lagdo Dam in northern Cameroon are said to have worsened the flood situation.

Experts say that the 2022 flooding was the worse in a decade, with 662 people reported to have lost their lives while over 2 million were displaced. Even Nigeria’s Minister of Humanitarian Affairs, Hajiya Sadiya Umar Farouk said that the country lost between US$3.79 billion to US$9.12 billion in economic damage due to the flooding.

In August last year, the Nigerian Meteorological Agency sounded the alarm, urging state and national emergency management agencies to intensify response mechanisms as massive flooding was expected in 19 states of the country between August and October. Sadly, there were no efforts to evacuate residents in Onyedega and surrounding communities that are most vulnerable to flooding.

Traditional Ruler of Ibaji, Dr. John Egwemi says his people are full of praise for the the LDSC and the CRS for the project

While available reports suggest that over 50,000 people in Ibaji–a coastal town were displaced and three persons killed by the flooding, residents say the casualty figure was more.

Hope restored

“Sometime this February, as I sat in front of my house, a team from the Justice Development and Peace Commission of Idah Diocese came and said that they wanted to register me for a flood assistance project, “said Egwuma. “I had doubts but I gave them my details and they left,”.

The project, known as the Emergency Assistance for People Affected by the Flood in Nigeria’, was implemented by Catholic Relief Services, an agency of the U.S Bishops with funding from the Latter-day Saint Charities (LDS Charities).

After two weeks, beneficiaries were selected, including Egwuma and bank accounts were opened in their names. Each of them received money in three batches to be used in the purchase of food and non-food items.

“I thought I was dreaming when I received the first transfer and then, the second and third ones came, “he said. “I was able to provide food for my family with the money, I also bought some rice seedlings and chemicals for my rice farm, including jerricans for water, and other household items that were washed away by the floods,”.

Anselm Nwoke, CRS’s partnership and capacity-strengthening coordinator in Nigeria explained that the flood assistance project was funded by Latter-day Saint Charities (LDS Charities), following a request from the Dioceses of Idah, which the NGO had been working with, to support them to respond to the flood.

“The main focus of the project was to enable people to recover from the effects of the flooding and it is part of our emergency response at the CRS,” he said. “But first, we responded with our private resources before we started seeking further assistance.”

Catholic Bishop of Idah Diocese, Most Rev Anthony Adaji says the project has restored lost hopes in Ibaji

CRS worked with community heads and church partners to select the most affected people, some of which includes female-headed households, pregnant and lactating mothers and very elderly people among others.

Like Egwuma, Ujah Japheth and her children escaped to Idah between October and November 2022, following the flood in her community which destroyed her house and the farmland where she cultivated 15 basins of Rice and 1600 Yam Tubers.

“It started gradually in August and I endured, but in October, it became serious and I ran to my sister’s house,”. She was helping to feed me because I could not do anything else,”.

Now, Ujah has gone back to her farm after she was selected and received flood assistance. With the money, she bought 400 Tubers of Yam and Four basins of Rice seedlings, Chemicals, water cans and cooking Utensils which the floods took away.

“I have also paid back some of the loans I took for my family’s upkeep while the flood lasted, I am happy I was part of the beneficiaries because I did not know how to get money after I lost everything,”.

Director of JDPC in Idah, Fr. Cyril Adama said that the benefitting households were chosen out of over 540 that were registered across three communities in Ibaji, including Onyedega, Iyano and Echeno in Odeke.

He said that they were selected using a participatory process, including clear targeting criteria and a scoring system based on the households’ vulnerability status index, after which the electronic platform, CommCare was used to facilitate the selection process.

Ogala Joseph is back to his Rice farm, thanks to the money he got from the flood assistance project

Community mobiliser/enumerator at JDPC, Ogwu Ibrahim said that at least 1500 individuals were positively affected.

Catholic Bishop of Idah Diocese, Most Rev Anthony Adaji said that the project has restored lost hopes in Onyedega which has experienced recurrent flooding without government intervention. He said that it shows how much the church cares about the welfare of the people.

Preparing for the floods

Ogala Joseph’s Rice had already started to germinate when the floods came and destroyed everything. He had planted 10 basins and 2000 Tubers of yam, hoping for a bountiful harvest.

“My house was submerged and almost everything inside it was destroyed, I only managed to take out my bed with which my family slept on the main road for two months,”.

“Within that period, life was difficult for me and my family because we did not have money to feed, “he said. “Severally, my children fell sick due to cold but I could not afford to treat them,”.

After the JDPC team took his data, he kept hope alive that he will be selected. And thankfully, he was. “When the money came in, I rushed and bought a Canoe for N50,000 to be able to access my farm and other areas in case the floods come again,” Joseph said. “I also used the money to buy food items and chemicals for my Rice farm,”.

A lifesaver

Ceceilia Ukwo started working on people’s farms with her seven children after the floods destroyed everything she had. Sometimes, they gave her food and money. But it was not enough to keep her family going.

She had lost her husband years ago and so, the bulk of the responsibility of taking care of the home rested on her shoulders. Three of her children were attending the Holy Angel Nursery and Primary School. She borrowed to pay their fees.

Ceceilia Ukwo used part of the assistance to buy chemicals for her Rice farm and clear her debts

One day, as she worked on her farmland, she received an alert but she did not know what it was. When she returned home and showed one of her neighbours who told her she had been credited by the JPDC under the flood relief fund project–she had been selected as a beneficiary.

“With the money, I paid back the loan hanging on my neck, “she said. “I also used it to buy Jerricans for fetching water for the house and Chemicals for my farm,”. “I am really happy because I did not know where to get the money”.

Traditional Ruler of Ibaji, Dr John Egwemi described the project as giving his people a sense of belonging and hope to live again after the destructive floods. He said that each time he returns home, his people ask him to thank the CRS and the LDSC for bringing back their joy.

“They have continued to express their appreciation to the non-profits for robbing smiles on their faces”. “Most of them are investing the money back into their farms with the hope of making profits, “he said.